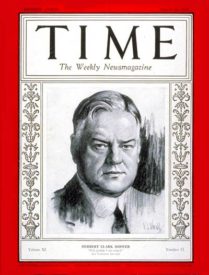

Herbert Hoover was worth $4 million in 1914 as a mining engineer and mine owner. This was before World War I, when the dollar bought 25 times more than it does today. He was good at what he did in the private sector.

Herbert Hoover was worth $4 million in 1914 as a mining engineer and mine owner. This was before World War I, when the dollar bought 25 times more than it does today. He was good at what he did in the private sector.

He gained national fame as a World War I relief administrator: Belgian relief. The Germans let him do this because it freed up food for the German Army: no need to feed occupied Belgium. This is now how the history books tell it. This was the next phase of the legend of “Hoover the Engineer.”

Harding appointed him Secretary of Commerce. Hoover then oversaw the nationalization of the airwaves. He created the Federal Radio Commission, which became the Federal Communications Commission. Instead of selling air space to the highest bidder — the free market solution — he let the FCC license and periodically re-license broadcasters. This became the basis of the second most important cartel after the banking cartel: the media cartel. This was the origin of the mainstream media.

Coolidge kept him on, but he had contempt for him. He called him the “wonder boy.” He once said: “That man has offered me unsolicited advice every day for six years, all of it bad.”

Then he became President. He became the heir of a boom created by the Federal Reserve System’s fiat money. His actions turned what would have been a sharp recession into a depression — a word he coined to replace “panic.”

He then started spending vast quantities of federal money. He also pressured businesses to hold up wages above the market wage levels, industry by industry. This created unemployment. His government created the Reconstruction Finance Corporation to provide government loans to high-risk businesses. Franklin Roosevelt retained the RFC.

The percentage increase of government spending under Hoover’s four years was greater than FDR’s during the first seven years.

Yet even Coolidge deserves some of the blame. Professor Randall Holcombe has described what happened under the Republicans, 1921-33.

If one looks only at total federal spending, it appears that the Republican administrations of Harding and Coolidge are a period of retrenchment sandwiched between the big-spending Democratic administrations of Woodrow Wilson and FDR. The Hoover administration does not fit this view even when examined superficially, because the percentage increase in spending during those four years exceeded the growth in the first seven years of FDR’s New Deal, before World War II caused spending to skyrocket. Despite the conventional wisdom that big government began with FDR, a closer examination reveals that even the Harding and Coolidge administrations were periods of substantial government growth. It was masked, though, by the reduction in war-related spending following World War I. The 1920s, then, were actually a continuation of Progressive Era government expansion, which would last through the New Deal.

Contemporary political-party ideological stereotypes do not fit the pre-New Deal era. At the risk of some oversimplification, they should be reversed. The Republican party, the party of Lincoln, was the advocate of a strong federal government with increasing powers, while the Democratic party, which had most of its power in the South, advocated states’ rights and a smaller federal government. Moreover, Harding and Coolidge were not particularly strong presidents, and the Congress was dominated by Republicans with substantial Progressive leanings. For Harding and, after Harding’s death in 1923, Coolidge, a return to normalcy meant a return to the Progressive policies begun before the war. This was even more true of Hoover, who was an engineer by training and a firm believer in applying scientific principles of management to government.

This is why New York Governor Franklin Roosevelt was taken seriously in his Fall 1932 Presidential campaign speech in Pittsburgh when he announced this:

For over two years our Federal Government has experienced unprecedented deficits, in spite of increased taxes. We must not forget that there are three separate governmental spending and taxing agencies in the United States the national Government in Washington, the State Government and the local government. Perhaps because the apparent national income seemed to have spiraled upward from about 35 billions a year in 1913, the year before the outbreak of the World War, to about 90 billions in 1928, four years ago, all three of our governmental units became reckless; and, consequently, the total spending in all three classes, national, State and local, rose in the same period from about three billions to nearly thirteen billions, or from 8 1/2 percent of income to 14 1/2 percent of income.

The problem was, he insisted, that high taxes cannot boost the economy.

“Come-easy-go-easy” was the rule. It was all very merry while it lasted. We did not greatly worry. We thought we were getting rich. But when the Crash came, we were shocked to find that while income melted away like snow in the spring, governmental expense did not drop at all.

This was part of Roosevelt’s grand deception. It worked. Then the speech went down the memory hole. So did Hoover’s Keynesian spending.

Hoover gets blamed for the Great Depression, not the Federal Reserve. He should be blamed for turning a sharp recession into the Great Depression. He did it by means of policies that were imported and then extended by the New Deal.

This is a good inoculation against the Keynesian textbook version of the story.

Written by Gary North for and published by Specific Answers ~ December 21, 2016.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml