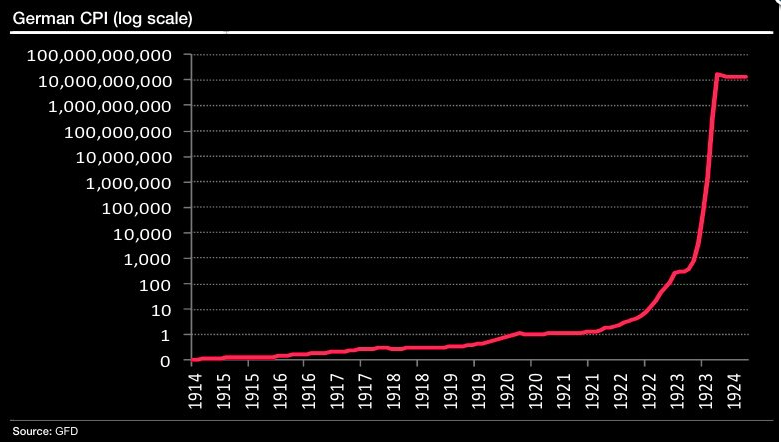

Weimar Germany after World War One went through one of the worst hyperinflations in history, unleashing untold horrors on the German people and their economy.

Memories of Weimar still haunt the eurozone today. The European Central Bank, widely considered to be the only institution with the firepower to stem the euro crisis, is somewhat restrained by the legacy of the German Bundesbank.

Memories of Weimar still haunt the eurozone today. The European Central Bank, widely considered to be the only institution with the firepower to stem the euro crisis, is somewhat restrained by the legacy of the German Bundesbank.

The Bundesbank – established in 1957 (well after Weimar) – for years before joining the euro was extremely conservative in expanding the money supply because of what happened during the Weimar years. And 90 years later, Germans are reminded of the perils of the printing press, whether or not the comparison is truly apt.

Adam Fergusson authored a book on the subject, entitled When Money Dies – and many consider it to be the definitive work on the Weimar hyperinflation.

It used to be out of print and a bit hard to find, but we summarized the key elements Fergusson’s book, which may be found it in its entirety online.

The inflation’s roots were in World War One, which Germany financed with outsized budget deficits

The inflation’s roots were in World War One, which Germany financed with outsized budget deficits

Germany hoped that it would quickly win the war and reap bounty from the nations it conquered, which – to the government – justified the use of the printing press to fund it:

It may have been true — there is no reason to doubt it — that a short, sharp war and a speedy victory in 1914 had been both hoped for and expected. Together with the prospect of eventual war indemnities extorted from the Entente, this would possibly have justified taking temporary liberties, even outrageous ones, with the known laws of finance…that was indeed how it did begin: in part the natural result of having a self- willed Army itching for war and a Federal Parliament which, though with limited power over the country’s constituent states, still had to find the money to pay for it.

During the war, the German government used extensive propaganda to hide the inflation from the population

During the war, the German government used extensive propaganda to hide the inflation from the population

The German government appealed to patriotism to fund the conflict, using slogans like “I gave gold for iron,” and “Invest in War Loan.”

Furthermore, it censored information heavily:

Every German stock exchange was closed for the duration, so that the effect of Reichsbank policies on stocks and shares was unknown. Further, foreign exchange rates were not published, and only those in contact with neutral markets such as Amsterdam or Zurich could guess what was going on…Only when the war was over, with the veil of censorship lifted but the Allied blockade continuing, did it become clear to all with eyes to read that Germany had already met an economic disaster nearly as shattering as her military one.

However, the growing economic hardship during the war caused many German soldiers to desert

However, the growing economic hardship during the war caused many German soldiers to desert

A German newspaper ascribed Germany’s loss of the war partly to the fact that men were abandoning the front to return home and support their families:

With the benefit of two years’ hindsight, The Vossische Zeitung could print in August 1921:

Our military defeat was due to the fact that for every 1000 men we had in the trenches, double that number of deserters and embusques remained at home. These deserters were activated less by military than economic motives. The rise in prices was mainly responsible for the poverty of the families of the enlisted men.

To make things worse, the Treaty of Versailles that ended the conflict imposed huge reparations on Germany

To make things worse, the Treaty of Versailles that ended the conflict imposed huge reparations on Germany

Not only did the Treaty of Versailles impose reparation demands that Germany would never realistically be able to repay, but it also annexed German territory and required the army to fire hundreds of thousands of soldiers:

The implications of these truncations for the German economy were of course enormous: and so were those of the requirement to reduce the German army to a quarter of its size, for it meant that over a quarter of a million more disbanded soldiers were to be thrown on the labour market. Work had to be found for them at any cost, or so it was calculated. What spelt doom were the clauses that made Germany responsible for the war and demanded colossal reparations — in money and in kind — to meet the Allies’ costs.

In the aftermath, the German political scene was wildly volatile, and assassinations were rampant

In the aftermath, the German political scene was wildly volatile, and assassinations were rampant

The right-wing and left-wing parties that emerged from the wreckage of the war were starkly opposed to each other, and it divided the country:

Some of the poison of northern militarism having, as it were, been drawn off, the disaffected, reactionary elements mainly took refuge in the hotbeds of the south. Bavaria then became the mainspring of Germany’s 400 political murders, mostly unpunished, many unsolved, between 1919 and 1923: the militarist Right may not have been responsible for more than the lion’s share of them, but those years were certainly an open season for the officials and supporters of the new Republic.

By September 1920, prices were 12 times as high as they had been before the war

By September 1920, prices were 12 times as high as they had been before the war

By the autumn of 1920, the strains on the economy in the wake of the war were apparent, but employment was still fairly strong:

Food had accounted for half the family budget then, but now nearly three-quarters of any family’s income went on it. The food for a family of four persons which cost 60 marks a week in April 1919, cost 198 marks by September 1920, and 230 marks by November 1920.

Certain items such as lard, ham, tea and eggs rose to between thirty and forty times the pre-war price. On the bright side – in contrast to Austria – the official unemployed figure was low, and only 375,000 people were on the dole.

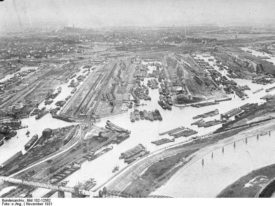

Duisberg, Germany

In March 1921, France occupied German ports because they couldn’t make reparations payments

Lord D’Abernon, the British ambassador to Berlin, warned the Allies that Germany would not be able to repay, but France insisted, and then occupied German ports:

[It was at] the Paris conference, at the end of January 1921, where France, herself not far from insolvency, began making demands on Germany which D’Abernon described quite simply as ‘amazing’. The figures that came out of Paris for German consideration, although nowhere near what the French had demanded, provoked shock in Germany…[By March,] France lost patience with the Germans and, by way of sanctions under the peace treaty, the Rhine ports of Duisburg, Ruhrort and Düsseldorf were occupied by the Allies.

Meanwhile, amid the economic gloom of the lower and middle classes, the rich were spending money like crazy

Meanwhile, amid the economic gloom of the lower and middle classes, the rich were spending money like crazy

To avoid high taxes, the rich instead spent as much money that they could. However, it highlighted the class divide in Germany, where lower income earners were having trouble getting by:

The extravagance of the rich one hears of is very sad, but it is said to be largely due to high taxation, as they feel that unless they spend it the government will get most of it…Unfortunately the persons from whom it is most difficult to collect taxes are those who most should pay, that is to say war profiteers and particularly traders in contraband goods who in many cases have not kept accounts.

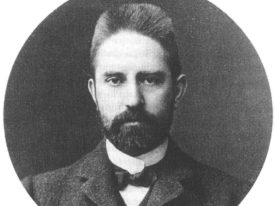

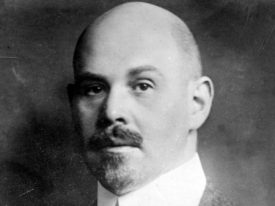

Matthias Erzberger

In August 1921, a major political assassination sent the German mark plunging

Matthias Erzberger, a Socialist leader who was a big proponent of taxation, was assassinated in August 1921.

The murder of Erzberger … undermined any remaining confidence that the German economy might be allowed to recover its health…bankers from Switzerland, Italy and Germany soberly concluded that it was impossible for Germany to continue her payments to the Entente and that sooner or later she would have to declare herself bankrupt, followed (they thought) by first France and then Italy. The mark, at 310 to the pound in mid-August, had sped downwards to over 400 by mid-September, and was still going down.

Meanwhile, anyone who could get their hands on foreign currency was selling the  mark

mark

Germans everywhere were doing everything they could to convert their marks into other currencies. A councillor at the British embassy in Berlin wrote:

Millions of persons in this country are, I think accurately, reported to be buying foreign currencies in anticipation of fresh tax burdens, and to be hoarding foreign bank notes…I hardly know a single German of either sex who is not speculating in foreign currencies, such as Austrian crowns, Polish marks and even Kerensky roubles. In as much also as a fall in the value of the mark is inevitably accompanied by a rise in the quotation of industrial shares, speculators are supposed to be operating systematically to depreciate the mark with a view to reaping the benefit of higher quotations in the share market.

As February of 1922 approached, it became clear that Germany wouldn’t be able to make its reparation payment

As February of 1922 approached, it became clear that Germany wouldn’t be able to make its reparation payment

In the inevitable event that Germany was not able to make good on the reparations to the Allies by the end of February, 1922, France would occupy a major economic region of Germany:

Germany now needed to find 500 million gold marks before the end of February to pay the Allies, and knew that she faced sanctions by France — the occupation of the Ruhr — in case of default. Default would come unless London helped. The London bankers, however, refused to give the necessary credits unless Germany put her financial house in order and unless French demands became more reasonable. Since no condition could apparently be met without the fulfilment of the others as its preconditions, German bankers now began to fear that the mark might fall to Austrian levels.

Meanwhile, goods were flying off the shelves of shops as people tried to protect themselves against the falling value of the currency

Meanwhile, goods were flying off the shelves of shops as people tried to protect themselves against the falling value of the currency

The scene described by Addison in Berlin shops in November of 1921 was chaotic:

Many shops declare themselves to be sold out. Others close from one to four in the afternoon, and most of them refuse to sell more than one article of the same kind to each customer. The rush to buy is now practically over as prices on the whole have been raised to meet the new level of exchange. In almost every camera shop, however, the sight of a Japanese eagerly purchasing is still a common feature. But on the whole, as far as Berlin is concerned, it is the Germans themselves who are doing most of the retail buying and laying in stores for fear of a further rise in prices or a total depletion of stocks.

German Reichsbank

However, a conference of Allied powers over reparations in December of 1921 offered Germany a glimmer of hope

It appeared at a conference in December that the Allied powers finally were realizing that holding Germany to the following year’s reparation payments were unrealistic. This led to a surge in the mark:

This consideration sent a wave of confidence crashing dangerously back through the exchanges — confidence that at last the intolerable blight on the financial system would be removed. On December 1, 1921, the mark soared upwards, regaining a quarter of its November value. By the time it reached 751 to the pound (against its November average of 1,041) the paper-mark prices of many stocks and shares, although still well above the levels of December 1920, had declined by half or more…while the Reichsbank was buying foreign currencies heavily.

But regardless of the politics, by Christmas 1921 ordinary Germans were feeling the squeeze of inflation

But regardless of the politics, by Christmas 1921 ordinary Germans were feeling the squeeze of inflation

By the end of 1921, workers had lost so much faith in the government that many just stopped voting. The economic hardships brought about by inflation were evident in everyday prices:

In the eight years since 1913, the price of rye bread had risen by 13 times; of beef by 17. Those were the commodities which had fared best. Sugar, milk (at 4.40 marks a litre), pork and even potatoes (at 1.50 marks a Ib.) had risen between 23 and 28 times; butter had gone up by 33 times. These were only the official prices — real prices were often a third higher — and all these prices were roughly half as much again as in October, only two months before.

The relative strength of the mark in 1921 foreshadowed what would come years later when the hyperinflation was finally stopped

The relative strength of the mark in 1921 foreshadowed what would come years later when the hyperinflation was finally stopped

When the mark was strong, companies went bankrupt as share prices plummeted. Thus, an inverse correlation was established:

The 1921 figures were the most indicative; for in comparing the number of bankruptcies during the various months of the year it could be shown that a falling mark was associated with a decline in bankruptcies, and vice-versa. The largest number, 845, was in the spring when the mark stood highest; but after it reached its lowest in November the number was 150. The Frankfurter Zeitung commented: ‘It gives some inkling of the awful debacle which may be expected if a rapid and permanent improvement of the mark actually takes place.’

Hugo Stinnes

The relationship between the strong mark and increased bankruptcies also highlighted class tension

Owners of large industrial conglomerates benefitted from the inflation, so they constantly reminded the populace that amid the economic chaos, employment was still very high:

Hugo Stinnes himself, the richest and most powerful industrialist in Germany, whose empire of over one-sixth of the country’s industry had been largely built on the advantageous foundation of an inflationary economy, paraded a social conscience shamelessly. He justified inflation as the means of guaranteeing full employment, not as something desirable but simply as the only course open to a benevolent government. It was, he maintained, the only way whereby the life of the people could be sustained…In the summer of 1922 the small businessman saw his enemy in the big businessman, personified by Herr Stinnes, ‘the greatest obstacle to currency reform’, as Lord D’Abernon described him.

Walter Rathenau

Then, in June of 1922, the German foreign minister, who was in favor of paying reparations, was assassinated

Walter Rathenau was a the German foreign minister, and he was often linked to the unpopular stance that Germany should find a way to pay its reparations. He was not trusted by the right-wingers in government.

Rathenau, a Jew like Erzberger, had just undergone, like Erzberger, a vitriolic attack in the Reichstag from the Rightist leader Dr Helfferich.

A few hours later, as Rathenau was driven from his home to the Foreign Office, the path of his car was blocked deliberately by another, while two assassins in a third car which had been following riddled him with bullets at close range. A bomb, thrown into his car for good measure, nearly cut his body in two.

This further worried the international community, and the mark plunged on the news.

This further worried the international community, and the mark plunged on the news.

And anti-Semitism in Germany was rising in general

The consul in Frankfort, Germany described a disturbing trend on the rise in 1922:

It is no exaggeration to say that cultured German men and women of high social standing openly advocate the political murder of Jews as a legitimate weapon of defence. They admit, it is true, that the murder of Rathenau was of doubtful advantage … but they say there are others who must go so that Germany shall be saved. Even in Frankfort, with a prepondering Jewish population, the movement is so strong that Jews of social standing are being asked to resign their appointments on the boards of companies …

In July, even the workers who printed new money went on strike, which led to crisis

In July, even the workers who printed new money went on strike, which led to crisis

A confidential memorandum prepared for the Chancellor of Germany regarding the incident indicated suspicion that someone behind the scenes was trying to impede the government’s ability to print money:

An extraordinary amount of paper money had been needed in June, causing the Reichsbank to issue 11,300 milliard marks in new notes. Owing to strikes, the usual inflow of these notes back into the bank had not happened, so that there were none in reserve…In spite of the readiness of the trade unions to go ahead with the new paper, the printers themselves suddenly withdrew their consent. ‘It was plain,’ said the memorandum, ‘that other forces were at work than a mere wage or sympathy strike. It seemed probable that hidden and illicit leaders were trying to seize the State by the throat.’

Then, in the middle of the crisis, the German government took an inopportune holiday, which sent the mark plunging again

Then, in the middle of the crisis, the German government took an inopportune holiday, which sent the mark plunging again

In a strange move, the German government decided to go on holiday, which destroyed confidence and exacerbated the crisis:

At what might otherwise have been the height of the immediate crisis at the end of July 1922, the Reparations Commission decided to take its summer holidays, effectively postponing any settlement of the exchange turmoil until mid-August; and [French prime minister] M. Poincare, bent as ever (it was believed) on Germany’s destruction, sent a Note to Berlin accusing the government of wilful default on its debts, and threatening ‘retortion’. The effect on the financial situation was calamitous. The rise in prices intensified the demand for currency, both by the State and by other employers…much business quickly came to a standstill. The panic spread to the working classes when they realised that their wages were simply not available.

Meanwhile, working class wages were rising faster than inflation, which squeezed the middle class

Meanwhile, working class wages were rising faster than inflation, which squeezed the middle class

The disadvantaged middle class was the class that maintained communication with the outside world, so foreigners’ view of the domestic situation in Germany was especially downbeat:

Since these were fixed according to the average rate paid to [a chauffeur’s] class of worker, [the chauffeur] was not suffering unduly except in so far as wage rises, a monthly occurrence by this time, always lagged a little behind price rises which took place weekly, if not daily. This was the case for the vast mass of artisans and workmen, but of course…the middle class, including officials and journalists, were far from being in the same satisfactory position. It was from this latter group…that foreigners mostly derived their information, which was why the accounts of the incidence of inflation published abroad were almost unrelievedly gloomy.

However, by the autumn of 1922, inflation started to outpace wages once again, and everyone felt the pain

However, by the autumn of 1922, inflation started to outpace wages once again, and everyone felt the pain

Inflation was soaring by Autumn of 1922, and the working class began to lose their edge:

Already, however, a new element had joined the economic crisis. For the first time the wages paid for labour began to lag behind the rise in prices, noticeably and seriously, in spite of everything the monopoly of the unions could do about it. President Ebert, pleading…to engineer a further moratorium on reparations, pointed out that the conditions of existence for the working population had become ‘completely impossible’, and that the downfall of Germany’s economic life was imminent.

And in September of 1922, prices for basic goods soared

And in September of 1922, prices for basic goods soared

Basic staples were becoming increasingly out of reach as the mark plunged and German consumers lost an extraordinary amount of purchasing power:

A litre of milk, which had cost 7 marks in April 1922 and 16 in August, by mid-September cost 26 marks. Beer had climbed from 5.60 marks a litre to 18, to 30. A single egg, 3.60 in April, now cost 9 marks. In only nine months… [the] weekly bill for an identical food basket had risen from 370 marks to 2,615.

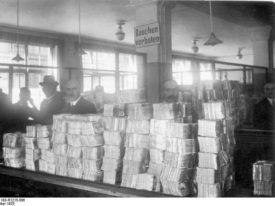

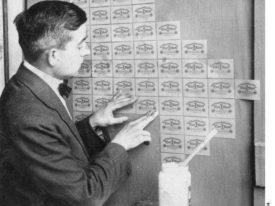

The soaring inflation led to currency chaos as everyone began to issue their own forms of money

The soaring inflation led to currency chaos as everyone began to issue their own forms of money

There was a major shortage of cash in spite of the German central bank’s wild expansion of the money supply. As a result, employers began issuing IOUs to workers all over:

Large industrial concerns began to pay their workmen partly in notes and partly in coupons of their own, which were accepted by local tradesmen on the understanding that they would be redeemed within a very short time. Municipalities, too, started to issue their own currencies, aware that any delay in receiving their pay packets would dangerously aggravate workers whose main concern was to spend them before they depreciated.

Raymond Poincaré

Then, in December, the French prime minister declared that France would occupy Germany the following month

Germany was clearly in no state to pay reparations, and France was angry. At a meeting in London, French Prime Minister Raymond Poincaré made his declaration:

That meeting, itself a preliminary to another in Paris, met in December to consider whether a moratorium on reparations ought to be granted. It was remarkable not merely for the presence of Signer Mussolini representing Italy, but for M. Poincare’s firm announcement to Mr Bonar Law that ‘Whatever happens, I shall advance into the Ruhr on January 15.’ It was France, not Britain who, in Sir Eric Geddes’s famous phrase of 1918 was intent on getting ‘everything out of Germany that you can get out of a lemon and a bit more,’ determined to ‘squeeze her until you can hear the pips squeak.’

Coal miner in the Ruhr

In January, France followed through with its threat, further devastating the German economy

France occupied the Ruhr, Germany’s coal and resource-rich industrial region as part of sanctions for not meeting reparation payments. German workers in the Ruhr resisted by striking:

Lacking an army big enough to take counter-measures, she riposted in the only way that came to mind: the policy of passive resistance in the newly occupied areas.

The industrial heart of Germany practically stopped beating. Hardly anyone worked: hardly anything ran…The German economy, however, called upon to subsidise an open-ended general strike, was not only denied its most important domestic products and raw materials — coal, coke, iron and steel in particular — but was robbed of its former enormous foreign earnings from Rhine-Ruhr exports. The Exchequer was itself deprived of all the normal tax revenue from a huge proportion of the nation’s industry, as well as the coal tax and the income from the Ruhr railways.

France’s occupation of the Ruhr region sent the Mark plummeting into real hyperinflation

France’s occupation of the Ruhr region sent the Mark plummeting into real hyperinflation

Along with economic devastation, Germany’s loss of the Ruhr was the straw that broke the camel’s back for the mark:

The Ruhr basin in 1923 provided nearly 85 per cent of Germany’s remaining coal resources, and 80 per cent of her steel and pig-iron production; accounted for 70 per cent of her traffic in goods and minerals; and contained 10 per cent of her population. The loss of the Ruhr’s production, and all it implied, was therefore a bale of last straws. At 35,000 to the pound at Christmas 1922, the mark fell to 48,000 on the day after the invasion, and at the end of January 1923 touched 227,500, well over 50,000 to the dollar.

And by the summer of 1923, food shortages were hitting Germany hard

And by the summer of 1923, food shortages were hitting Germany hard

The domestic situation in Germany resulting from the French occupation led to a full-blown food emergency by August of 1923:

On August 10, on which date a printers’ strike broke out to the further interruption of the supply of banknotes, the full weight of the shortage of paper money was felt. Stocks of food disappeared entirely in many communities, and factories were able to pay wages on account only. The railway workers in the British zone, with a wage tariff half that of factory workers, attempted to join the passive resisters of the Ruhr, and asked pathetically whether, if they were not allowed to strike, they could at least be guaranteed by the occupation authorities enough food at fixed prices as well as the money to buy it.

By then, Germans were afraid that France might even invade the German capital

By then, Germans were afraid that France might even invade the German capital

Complete and total gloom and fear of further conflict with France, which provided a backdrop that helped Hitler rise to power:

Despair, indeed, was consuming Germany. It was believed that the disturbances in the Ruhr and the Rhineland might lead to the French marching upon Berlin; and the French did not discourage such talk. Violent Communist-led outbreaks were occurring in Saxony and Thuringia, and the reactionary movement under Hitler in Bavaria was palpably growing in strength and size.

At the end of September of 1923, the German Chancellor declared a state of emergency and put Germany under military rule

At the end of September of 1923, the German Chancellor declared a state of emergency and put Germany under military rule

Seeing the waning confidence of German workers in the Ruhr and Hitler’s rise to power in the Bavarian region, the German chancellor took decisive action to maintain control of the situation:

On September 26 [Chancellor Stresemann] suspended seven articles of the Weimar constitution, himself declared a State of Emergency…Germany had become a military dictatorship, no less, and by the choice, at that, of a largely Socialist cabinet. The country was divided into seven military districts, with a local military dictator over each. Simultaneously President Ebert announced the end of passive resistance in the Ruhr.

Young Adolph Hitler

However, it was clear by October that Bavaria was out of the hands of the central government in Berlin

Bavaria, where Hitler was active, showed no deference to Berlin or the chancellor, setting the stage for more internal conflict:

Although Munich and the municipalities of Bavaria were suffering no more than the same economic rigours as anywhere else, it was evident that here was the most explosive mixture in Germany…New decrees were issued daily prohibiting public meetings and strikes, and there was no doubt that the two authoritarian friends, von Kahr and General von Lossow, were in full control. So confident were they, indeed, that they were calculatingly ignoring instructions received from Berlin. Their posture even went to the lengths of refusing Berlin’s order to ban Hitler’s newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter, on October 2, but none the less suspending it for ten days from October 5 for publishing a treasonable article.

Finally, in November of 1923, the German government took action to stabilize the currency

Finally, in November of 1923, the German government took action to stabilize the currency

The German government set up the Rentenbank to issue a new currency, the Rentenmark, which would be backed by land and industrial goods.

The Rentenmark finally stabilized the German currency:

As it was, the confidence trick worked. The Rentenmark, the stopgap designed to shift the 1923 harvest, became the weapon which held the field for the billion-mark note until the Reichsmark was brought in a year later. ‘On the basis’, said Bresciani-Turroni, ‘of the simple fact that the new paper money had a different name from the old, the public thought it was something different from the paper mark … The new money was accepted, despite the fact that it was an unconvertible paper currency.It was held and not spent as rapidly.

And the next month, in December, the food shortages of the summer finally began to recede

Finally, a month after the Rentenmark was introduced, everyday Germans were able to feed themselves again:

Food, however, was beginning to appear again in the towns half way through December; and to the Rentenmark alone was this development due. In 1923, before November, the only increase in animals slaughtered for food had occurred in dogs:* (Mainly used to supply a deficiency in pork.) after stabilisation, the consumption of every article of daily need — beer, pork, coffee, sugar, tobacco — increased regularly, except dogmeat.

However, after a recovery in 1924, a whole new crisis hit Germany in 1925 – mass unemployment

However, after a recovery in 1924, a whole new crisis hit Germany in 1925 – mass unemployment

The strengthened currency and subsiding hyperinflationary pressures once again brough German industry to its knees as several firms plunged into bankruptcy, and unemployment soared:

The picture in the first week of December 1925 presented the politicians’ nightmare of 1922: the approach of the genuine, unhidden mass unemployment that the policy of inflation had so largely been designed to avoid. The mark stood steady…By February 1926 the number of registered unemployed soared over 2 million, with depression reaching from Hamburg to Bavaria. The average number of registered unemployed stayed at over 2 million throughout 1926 — otherwise a year of rationalisation, and of economic and industrial recovery — and was still at nearly 1.5 million in December.

This was hugely demoralizing for Germany, which thought it had already been through the worst and was staging a recovery.

And this shock brought increasing divergence between the fortunes of the middle and lower classes

And this shock brought increasing divergence between the fortunes of the middle and lower classes

With the new crisis, the tables were turned – the lower classes found themselves unemployed while the middle classes did relatively well:

By May of that year the circumstances of doctors, lawyers, professors and writers and the like had radically changed. They were again able to live in circumstances appropriate to their cultural environment: their fees were being paid, and their services were required in full measure…Only the legions of unemployable whose substance had been dissipated and the hundreds of thousands of workers for whom there was no work bore the outward scars of the great inflation and spoilt an otherwise happy picture.

But post-war Germany never fully recovered, and mass unemployment eventually allowed Hitler to rise to power

But post-war Germany never fully recovered, and mass unemployment eventually allowed Hitler to rise to power

Hitler leveraged the mass unemployment to gain support for the Nazi party and quickly rose to political power in the 1930s:

To say that inflation caused Hitler, or by extension that a similar inflation elsewhere than in a Weimar Germany could produce other Right or Left wing dictatorships, is to wander into quagmires of irrelevant historical analogy…On the other hand, the vast unemployment of the early 1930s gave Hitler the votes he needed. Just as the scale of that unemployment was part of the economic progression originating in the excesses of the inflationary years, so the considerable successes of the Nazi party immediately after stabilisation and immediately before the recession were linked (pace the observations of the Consul-General Clive) with its advances in 1922 and 1923.

For Further Considerations on this Topic: Click HERE (Ed)

Written by Matthew Boesler and published by Business Insider ~ October 21, 2012.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml