1935 (Lib. of Congress)

For Shakespeare the seven ages of man moved from the fifth, the established man of “Justice,” to the sixth, “the lean and slippered Pantaloon / With spectacles on nose and pouch on side,” essentially a wealthy fool, to the seventh, “second childishness and mere oblivion / Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” Modern Americans might ask: But where is Retiree with golf club and RV?

This stage of life, which most Americans not only recognize but strive to enjoy (“having fun spending the kids’ inheritance,” reads one bumper sticker), typically commences with a distinct move, formally leaving the workforce and beginning to collect a pension. Giving up work at an advanced age is not new, but this official stage is a twentieth-century invention. Indeed, the phrase “retirement age” hardly ever appeared in American writing until the 1920s and then it became commonplace.[1]

The story of how twentieth-century economic and political change altered what Shakespeare described as an eternal cycle of life from “the infant / Mewling and puking” to the “second childishness” underlines the social malleability of what seems “natural.”

Dropping Out

Historically, men worked less and less as their bodies weakened or as jobs became harder to find. Some did well; one study found that about a fifth of American men in the early 1900s retired voluntarily with some savings.[2] But for most, aging meant involuntarily ceasing or reducing work; if lucky, it also meant living with, hopefully while being useful to, an adult child. For less fortunate others, it meant an eventual move to the almshouse (which spurred laws requiring children to take care of their elderly parents). For almost all, no particular year or transition–unless it was accident or illness–marked a change in life stage.

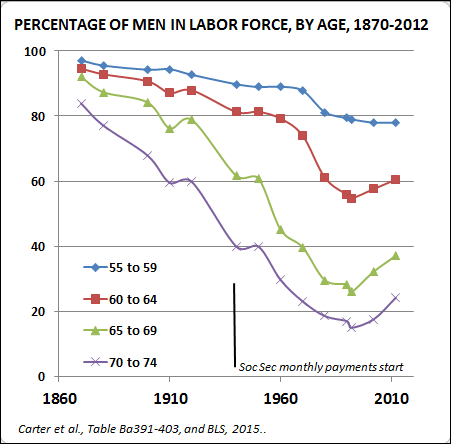

The graph below shows rates of men’s labor force participation, by age, from 1870 to 2012.[3] (The history for women reflects so many other developments that I bracket them here.) A few things are evident in the trends. In the late nineteenth century, 80 percent or more of men from ages 55 to 74 were in the labor force. And there was not much difference in rates between men in their late 50s and men 15 years older. By the late twentieth century, working rates had dropped greatly, mainly because now fewer than a third of men age 65 and older worked. That decline was particularly steep for men 65 and older.

The decline in men’s labor force participation had started before the 1935 passage of the Social Security old-age pension program. An improving economy, a shift of jobs from farm to factory, employers’ age limits, early forms of business, military, and civil service pensions pushed and pulled older men out of work from the 1880s through 1930s. (Of course other events, such as depression, recession, and war also affected working rates.) Some of the early, small pension systems for the elderly crumbled in the Great Depression, which helped fuel the New Deal campaign for a federal pension. We see signs in the data of how, especially after 1950 or so when benefits increased, retirement developed as a distinct life stage; the difference in participation rates between men in the oldest group and in the youngest roughly doubled between 1920 and 1970. Sixty-five, give or take a couple of years, became a meaningful threshold to a new phase of life, one large enough to drive an RV through.

The decline in men’s labor force participation had started before the 1935 passage of the Social Security old-age pension program. An improving economy, a shift of jobs from farm to factory, employers’ age limits, early forms of business, military, and civil service pensions pushed and pulled older men out of work from the 1880s through 1930s. (Of course other events, such as depression, recession, and war also affected working rates.) Some of the early, small pension systems for the elderly crumbled in the Great Depression, which helped fuel the New Deal campaign for a federal pension. We see signs in the data of how, especially after 1950 or so when benefits increased, retirement developed as a distinct life stage; the difference in participation rates between men in the oldest group and in the youngest roughly doubled between 1920 and 1970. Sixty-five, give or take a couple of years, became a meaningful threshold to a new phase of life, one large enough to drive an RV through.

The era of financially-secure retirement has, in turn, allowed a new life style for the aged. Poverty rates dropped greatly. And most retirees now live apart from their children.[4] As historians Carole Haber and Brian Gratton put it, “Social Security … brought to an end the expectation that work was the natural condition of life for the elderly…. [T]he history of the older worker has given way to the history of retirement.”[5]

The “golden years” tint to the retirement stage of life has faded recently as concerns have mounted about the financial security of older Americans. The private sources of retirement support, such as company pensions and investments, have weakened [6]; public sources of aid are under strain from a lower birth rate, a stagnating economy, and political retrenchment. And the years that such support must cover are growing. In 1990 a 65-year-old man could expect to live about 15 more years; in 2010, 18 more years. That’s an extra 20 percent of financing needed.

The age of man (and woman) that is retirement still entails risks. Nonetheless, it has in the last century become a definite stage of life for Americans. Its history points our attention to other stages of life that seem to have become distinctive over the last few generations. Scholars have long discussed early twentieth-century psychologists’ “invention of adolescence” with its special teen-age turmoil and syndromes. There is much talk these days about “emerging adulthood” as a liminal, stressful period between adolescence and settling down. There may be yet other candidates for new ages of man–empty nest?–as well.

Retirement remains particularly notable for the quasi-official way it was created, is sustained, and is symbolized–gold watch, a Medicare card, and that monthly check.

~ NOTES ~

1. Google ngram.

2. Carter and Sutch, “Myth…,” J. of Econ. History 56.

3. Carter et al., Historical Statistics of the United States, Millennial Edition and Bureau of Labor Statistics for 1992-2012 data.

4. E.g., McGarry and Schoeni, “Social Security…Elderly Widows’ Independence…,” Demography 37.

5. Haber and Gratton, Old Age and the Search for Security, p. 115. See also, Lee, “Labor Market Status of Older Males…,” Social Science History 29.

6. E.g., Hacker, The Great Risk Shift; Poterba, “Retirement Security…,” Am. Econ. Review 104.

Written by Claude Fischer and published by Made in America ~ May 13, 2015.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml