… and that means trouble – with a capital “T”

Not only does the US government never pay back what it has borrowed, somehow the emergency stimulus spending always becomes the new normal.

It just took a couple of weeks for the world to go from business-as-usual to dark-even-for-a-scifi-movie. It wasn’t long ago that people worried about things like doing their jobs, taking classes, and planning summer vacations. Now we all wonder how long we can stay in our homes before losing our sanity, how we can make a living and pay the bills, and even where we can find toilet paper. And everywhere we turn, it’s all coronavirus all the time.

It just took a couple of weeks for the world to go from business-as-usual to dark-even-for-a-scifi-movie. It wasn’t long ago that people worried about things like doing their jobs, taking classes, and planning summer vacations. Now we all wonder how long we can stay in our homes before losing our sanity, how we can make a living and pay the bills, and even where we can find toilet paper. And everywhere we turn, it’s all coronavirus all the time.

It feels for all the world that it’s the end of the world.

And while things are bad, maybe even grim for some, it’s not the end of the world. Supply lines are coming back online, cities have not descended into violence or madness, and people are genuinely helping their neighbors and trying to make the best of a bad situation. But that message gets lost when the talking heads start talking

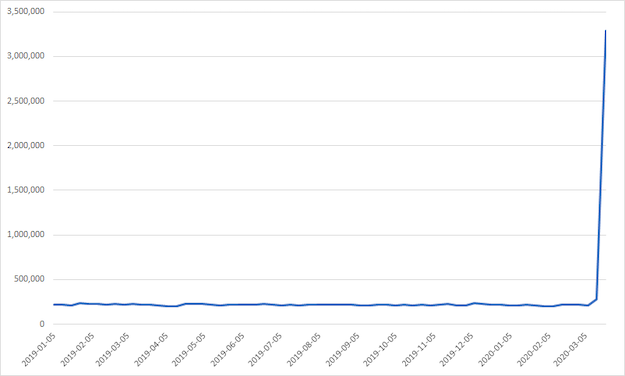

Nowhere was it lost as completely as when the initial jobless claims number rolled in following the country’s shuttering of most of its doors. That number, which is routinely in the neighborhood of 225,000, came in at a whopping 3.3 million in the first week after the government-mandated economic shutdown, and another 6.6 million in the second week. As bad as that is—and it is bad—it is not as bad as it might seem. A little historical perspective goes a long way here.

Initial jobless claims ~ Source: St. Louis Fed

Initial jobless claims is the number of workers collecting unemployment benefits for the first time. It’s a useful tool in the same way that a thermometer is a useful tool: It can give us a clear measure of one aspect of our economic health. But, like a thermometer, initial jobs claims doesn’t give us a complete picture of what’s going on. A second metric, continuing jobless claims, provides a different view by registering the number of workers collecting unemployment benefits for the second (or more) week in a row. A third, the number of unemployed, registers the number of people who are out of work, but looking for jobs, regardless of whether they are collecting unemployment benefits. As no physician would evaluate a patient’s health based solely on a thermometer reading, economists can’t evaluate an economy’s health based only on one (or even all three) of these measures.

It is alarming to see initial jobless claims balloon to 15 times, then 30 times, its normal size. But the spike was partly due to the fact that many people lost their jobs all at the same time. A typical recession lasts around 40 weeks. Had the same number of people lost their jobs in a staggered manner over the course of 16 weeks—as would have been more likely in a normal recession—we would have endured initial jobless claims of around 615,000 per week. That’s about what happened at the height of the 2008 recession, when initial jobs claims exceeded 615,000 per week for 15 weeks. The huge spike is only partially indicative of a large problem. It’s also largely indicative of the fact that the problem came upon us all at once rather than over a period of weeks.

While jobless claims numbers come out weekly, official unemployment numbers come out monthly (the next release is April 3). Adding the 6.6 million in initial jobless claims to last month’s unemployment numbers yields an unemployment rate of around 9.5 percent. That’s just below the peak unemployment rate of 10 percent in October 2009. The bad news is that this is a massive uptick from the previous month. The good news is that last month’s unemployment rate, 3.5 percent, was quite low.

Not only does the government never pay back what it has borrowed, somehow the emergency stimulus spending always becomes the new normal.

So it’s not the end of the world, at least not yet. But that’s not to say that things are tolerable at present, and it’s not to say they might not get a good deal worse before they get any better.

Again, some historical perspective helps.

From the end of the Bush administration through the first years of the Obama administration, the federal government spent (or failed to collect due to reduced taxes) a total of $2.8 trillion in stimulus money (more than $3 trillion in today’s dollars). That includes the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, TARP (the troubled asset relief program), “cash for clunkers,” and miscellaneous other bailouts and stimuli.

Then, as now, the federal government couldn’t afford the stimulus, so it borrowed. That’s behavior every household understands. In good times, you save money for rainy days. As was the case in 2008, we’re facing rainy days. Of course, the government doesn’t have any savings, so it must borrow. But, again, this is behavior every household understands. When times are tough, you borrow if you must, then you pay back when times are better. You have to put food on the table regardless of your immediate financial condition.

That’s where the government and the common-sense household part company. Because not only does the government never pay back what it has borrowed, somehow the emergency stimulus spending always becomes the new normal. When the emergency fades, the elevated spending doesn’t. From the Reagan years through 1999, the federal debt increased by around $475 billion (in today’s dollars) each year. In response to 9/11, the government boosted spending to deal with the new threat. Annual spending jumped up, but it never dropped back down. Annual debt growth after 9/11 was around 45 percent greater than it was before the attacks.

Starting in 2002, the debt grew by around $700 billion (again, in today’s dollars) each year. Then came the 2008 crash. The government boosted spending as part of the stimulus and bailouts. Again, annual spending jumped up, but never dropped back down. Annual debt growth after 2008 was around 80 percent greater than after 9/11, which was 45 percent greater than before 9/11. Starting in 2008, the debt has grown by around $1.3 trillion per year.

Thus far, it looks like the government will add more than $3 trillion to the debt in 2020. If politicians stay true to their history, that $3 trillion per year will become the new new normal. Where will the government turn to borrow this money?

The federal government’s largest creditor is the Social Security trust fund. But the trust fund not only has no more money to loan the government, it needs back the trillions it previously loaned the government to make good on promised Social Security benefits. Given the state of the world economy, the federal government likely can’t expect a helping hand from foreigners or even from Americans. That leaves one place. The lender of last resort is the Federal Reserve. But when the Federal Reserve loans money, the money supply increases. And that means that the new new normal will come with annual increases in the money supply. How much is unclear. But if the government had been on track to borrow more than $1 trillion per year prior to the virus, and now will be on track to borrow around $3 trillion per year, a reasonable guess is that at least $1 trillion per year will come from the Federal Reserve. Other things equal, that will cause significant inflation.

But immediate problems are immediate problems. The first thing we need to do is to get Americans back to work, and that’s going to take some time. It’s not as if a President can simply make a pronouncement that will magically change everything. It took a full decade for us to recover fully from the Great Recession of 2008, and we should expect the next recovery to take quite a long time too. The new new normal, on the other hand, is a wolf dressed in wolf’s clothing.

Neel Kashkari, president of the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank, went on 60 Minutes not long ago (see below) to say that “there is an infinite amount of cash in the Federal Reserve. We will do whatever we need to do to make sure there’s enough cash in the banking system.” That should be enough to make anyone concerned with the US monetary system flinch. Because if there is an infinite supply of anything, that thing isn’t worth much, by definition.

This is the dangerous game American politicians and bureaucrats are playing. It might well be necessary under the circumstances, but here’s the rub: When it comes time to move back to pre-catastrophe levels of spending, the politicians will find a way not to. Just as we never got back to pre-2008 levels, or pre-9/11 levels, we will never get back to pre-coronavirus levels. And when we pay the price in inflation, that will be why.

Written by Antony Davies and James R. Harrigan for the Foundation for Economic Education ~ April 7, 2020