As we reach the end of the year we find it of interest to study and understand the history of gold manipulation and its effect on global economics. ~ Ed.

By the end of 1925, Montagu Norman and the British Establishment were seemingly monarch of all they surveyed. Backed by Strong and the Morgans, the British had had everything their way: they had saddled the world with a new form of pseudo gold standard, with other nations pyramiding money and credit on top of British sterling, while the United States, though still on a gold-coin standard, was ready to help Britain avoid suffering the consequences of abandoning the discipline of the classical gold standard.

By the end of 1925, Montagu Norman and the British Establishment were seemingly monarch of all they surveyed. Backed by Strong and the Morgans, the British had had everything their way: they had saddled the world with a new form of pseudo gold standard, with other nations pyramiding money and credit on top of British sterling, while the United States, though still on a gold-coin standard, was ready to help Britain avoid suffering the consequences of abandoning the discipline of the classical gold standard.

But it took little time for things to go very wrong. The crucial British export industries, chronically whipsawed between an overvalued pound and rigidly high wage rates kept up by strong, militant unions and widespread unemployment insurance, kept slumping during an era when worldwide trade and exports were prospering. Unemployment remained chronically high. The unemployment rate had hovered around 3 percent from 1851 to 1914. From 1921 through 1926 it had averaged 12 percent; and unemployment did little better after the return to gold. In April 1925, when Britain returned to gold, the unemployment rate stood at 10.9 percent. After the return, it fluctuated sharply, but always at historically very high levels. Thus, in the year after return, unemployment climbed above 12 percent, fell back to 9 percent, and jumped to over 14 percent during most of 1926. Unemployment fell back to 9 percent by the summer of 1927, but hovered around 10 to 11 percent for the next two years. In other words, unemployment in Britain, during the entire 1920s, lingered around severe recession levels.

The unemployment was concentrated in the older, previously dominant, and heavily unionized industries in the north of England. The pattern of the slump in British exports may be seen by some comparative data. If 1924 is set equal to 100, world exports had risen to 132 by 1929, while Western European exports had similarly risen to 134. United States exports had also risen to 130. Yet, amid this worldwide prosperity, Great Britain lagged far behind, exports rising only to 109. On the other hand, British imports rose to 113 in the same period. After the 1929 crash until 1931, all exports fell considerably, world exports to 113, Western European to 107, and the United States, which had taken the brunt of the 1929 crash, to 91; and yet, while British imports rose slightly from 1929 to 1931 to 114, its exports drastically fell to 68. In this way, the overvalued pound combined with rigid downward wage rates to work their dire effects in both boom and recession. Overall, whereas, in 1931, Western European and world exports were considerably higher than in 1924, British exports were very sharply lower.

Within categories of British exports, there was a sharp and illuminating separation between two sets of industries: the old, unionized export staples in the north of England, and the newer, relatively nonunion, lower-wage industries in the south. These newer industries were able to flourish and provide plentiful employment because they were permitted to hire workers at a lower hourly wage than the industries of the north. Some of these industries, such as public utilities, flourished because they were not dependent on exports. But even the exports from these new, relatively nonunionized industries did very well during this period. Thus from 1924 to 1928–29, the volume of automobile exports rose by 95 percent, exports of chemical and machinery manufactures rose by 24 percent, and of electrical goods by 23 percent. During the 1929–31 recession, exports of these new industries did relatively better than the old: machinery and electrical exports falling to 28 percent and 22 percent respectively below the 1924 level, while chemical exports fell only to 5 percent below and automobile exports remained comfortably in 1931 at fully 26 percent above 1924.

On the other hand, the older, staple export industries, the traditional mainstays of British prosperity, fared very badly in both these periods of boom and recession. The nonferrous metal industry rose only slightly by 14 percent by 1928–29 and then fell to 55 percent of 1924 in the next two years. In even worse shape were the once-mighty cotton and woolen textile industries, the bellwethers of the Industrial Revolution in England. From 1924 to 1929, cotton exports fell by 10 percent, and woolens by 20 percent, and then, in the two years to 1931, they plummeted phenomenally, cottons to 50 percent of 1924 and woolens to 46 percent. Remarkably, cotton and woolen exports were at this point their lowest in volume since the 1870s.

Perhaps the worst problem was in the traditionally prominent export, coal. Coal exports had declined to 69 percent of 1924 volume in 1931; but perhaps more ominously, they had fallen to 88 percent in 1928–29, slumping, like textiles, in the midst of worldwide prosperity.

So high were British price levels compared to other countries, in both of these periods, that Britain’s imports, remark ably, rose in every category during boom and recession. Thus, imports of manufactured goods into Britain rose by 32.5 percent from 1924 to 1928–29, and then rose another 5 percent until 1931. So costly, too, was the once-proud British iron and steel industry that, after 1925, the British, for the first time in their history, became net importers of iron and steel.

The relative rigidity of wage costs in Britain may be seen by comparing their unit wage costs with the U.S., setting 1925 in each country equal to 100. In the United States, as prices fell about 10 percent in response to increased productivity and output, wage rates also declined, falling to 93 in 1928, and to 90 in 1929. Swedish wages were even more flexible in those years, enabling Sweden to surmount without export depression and return to gold at the prewar par. Swedish wage rates fell to 88 in 1928, 80 in 1929, and 70 in 1931. In Great Britain, on the other hand, wage rates remained stubbornly high, in the face of falling prices, being 97 in 1928, 95 the following year, and down to only 90 in 1931. In contrast, wholesale prices in England fell by 8 percent in 1926 and 1927, and more sharply still thereafter.

The blindness of British officialdom to the downward rigidity of wage rates was quite remarkable. Thus, the powerful deputy controller of finance for the Treasury, Frederick W. Leith-Ross, the major architect of what became known as the “Treasury view,” wrote in bewilderment to Hawtrey in early August 1928, wondering at Keynes’s claim that wage rates had remained stable since 1925. In view of the substantial decline in prices in those years, wrote Leith-Ross, “I should have thought that the average wage rate showed a substantial decline during the past four years.” Leith-Ross could only support his view by challenging the wage index as inaccurate, citing his own figures that aggregate payrolls had declined. Leith-Ross doesn’t seem to have realized that this was precisely the problem: that keeping wage rates up in the face of declining money may indeed lower payrolls, but by creating unemployment and the lowering of hours worked. Finally, by the spring of 1929, Leith-Ross was forced to face reality, and conceded the point. At last, Leith-Ross admitted that the problem was rigidity of labor costs:

If our workmen were prepared to accept a reduction of 10 percent in their wages or increase their efficiency by 10 per- cent, a large proportion of our present unemployment could be overcome. But in fact organized labor is so attached to the maintenance of the present standard of wages and hours of labor that they would prefer that a million workers should remain in idleness and be maintained permanently out of the Employment Fund, than accept any sacrifice. The result is to throw on to the capital and managerial side of industry a far larger reorganization than would be necessary: and until labor is prepared to contribute in larger measure to the process of reconstruction, there will inevitably be unemployment.

Leith-Ross might have added that the “preference” for unemployment was made not by the unemployed themselves but by the union leadership on their alleged behalf, a leadership which itself did not have to face the unemployment dole. More- over, the willingness of the workers to accept this deal might have been very different if there were no generous Employment Fund for them to tap.

It was in fact the highly militant coal miners’ union, led by the prominent leftist Aneurin “Nye” Bevan, that was the first to stir up grave doubt about the glory of the British return to gold. Not only was coal a highly unionized export industry located in the north, but already overinflated coal-mining wages had been given an extra boost during the first Labor government of Ramsay MacDonald, in 1924. In addition to the high wage rates, the miners’ union insisted on numerous cost-raising restrictive, featherbedding practices, some of them resurrected from the defunct postmedieval guilds. These obstructionist tactics helped rigidify the British economy, preventing changes and adaptations of occupation and location, and hampering rationalizing and innovative managerial practices. As Professor Benham trenchantly pointed out:

Employers who wished to make changes had to face the powerful opposition of organized labor. The introduction of new methods, such as the “more looms to a weaver” system, was resisted. Strict lines of demarcation between occupations were maintained in engineering and elsewhere. A plumber could repair a pipe conveying cold water; if it conveyed hot water, he had to call in a hot water engineer. Entry into certain occupations was rendered difficult. A man can become an efficient building operative in a few months; an apprenticeship of four years was required. British railways could not have their labour force as they chose. A host of restrictions, insisted upon by the Trade Unions, made this impossible.

By 1925, the year of the return to gold, British coal was already facing competition of rehabilitated, newly modernized, low-cost coal mines in France, Belgium, and Germany. British coal was no longer competitive, and its exports were slumping badly. The Baldwin government appointed a royal commission, headed by Sir Herbert Samuel, to study the vexed coal question. The Samuel Commission reported in March 1926, urging that miners accept a moderate cut in wages, and an increase in working hours at current pay, and suggesting that a substantial number of miners move to other areas, such as the south, where employment opportunities were greater. But this was not the sort of rational solution that would appeal to the spoiled, militant unions, who rejected those proposals and went on strike, thereby generating the traumatic and abortive general strike of 1926.

The strike was broken, and coal-mining wages fell slightly, but the victory for rationality was all too pyrrhic. Keynes was able to convince the inflationist press magnate, Lord Beaverbrook, that the miners were victims of a Norman–Churchill–international banker conspiracy to profit at the expense of the British working class. But instead of identifying the problem as inflationism, cheap money, and the gold bullion–gold-exchange standard in the face of an overvalued pound, Beaverbrook and British public opinion pointed to “hard money” as the villain responsible for recession and unemployment. Instead of tightening the money supply and interest rates in order to preserve its own created gold standard, the British Establishment was moved to follow its own inclinations still further: to step up its disastrous commitment to inflation and cheap money.

During the general strike, Britain was forced to import coal from Europe instead of exporting it. In olden times, the large fall in export income would have brought about a severe liquidation of credit, contracting the money supply and lowering prices and wage rates. But the British banks, caught up as they were in the ideology of inflationism, instead expanded credit on a lavish scale, and sterling balances piled up on the continent of Europe. “Instead of a readjustment of prices and costs in England and a breaking up of the rigidities, England by credit expansion held the fort and continued the rigidities.”

The massive monetary inflation in Britain during 1926 caused gold to flow out of the country, especially to the United States, and sterling balances to accumulate in foreign countries, especially in France. In the true gold-standard days, Britain would have taken all this as a furious signal to contract and tighten up; instead it persisted in continuing inflationism and cheap money, lowering its crucial “bank rate” (Bank of England discount rate) from 5 percent to 4.5 percent in April 1927. This action further weakened the pound sterling, and Britain lost $11 million in gold during the next two months.

France’s important role during the gold-exchange era has served as a convenient whipping boy for the British and for the Establishment ever since. The legend has it that France was the spoiler, by returning to gold at an undervalued franc (pegging the franc first in 1926, and then officially returning to gold two years later), consequently piling up sterling balances, and then breaking the gold-exchange system by insisting that Britain pay in gold. The reality was very different. France, during and after World War I, suffered severe hyperinflation, fueled by massive government deficits. As a result, the French franc, classically set at 19.3¢ under the old gold standard, had plunged down to 5¢ in May 1925, and accelerated its decline to 1.94¢ in late July 1926. By June 1926, Parisian mobs protesting the runaway inflation and depreciation surrounded the Chamber of Deputies, threatening violence if former Premier Raymond Poincaré, known as a staunch monetary and fiscal conservative, was not returned to his post. Poincaré was returned to office July 2, pledging to cut expenses, balance the budget, and save the franc.

Armed with a popular mandate, Poincaré was prepared to drive through any necessary monetary and fiscal reforms. Poincaré’s every instinct urged him to return to gold at the prewar par, a course that would have been disastrous for France, being not only highly deflationary but also saddling French taxpayers with a massive public debt. Furthermore, returning to gold at the prewar par would have left the Bank of France with a very low (8.6-percent) gold reserve to bank notes in circulation. Returning at par, of course, would have gladdened the hearts of French bondholders as well as of Montagu Norman and the British Establishment. Poincaré was talked out of this path, however, by the knowledgeable and highly perceptive Emile Moreau, governor of the Bank of France, and by Moreau’s deputy governor, distinguished economist Charles Rist. Moreau and Rist were well aware of the chronic export depression and unemployment that the British were suffering because of their stubborn insistence on the prewar par. Finally, Poincaré reluctantly was persuaded by Moreau and Rist to go back to gold at a realistic par.

When Poincaré presented his balanced budget and his monetary and financial reform package to Parliament on August 2, 1926, and drove them through quickly, confidence in the franc dramatically rallied, pessimistic expectations in the franc were changed to optimistic ones, and French capital, which had understandably fled massively into foreign currencies, returned to France, quickly doubling its value on the foreign exchange market to almost 4¢ by December. To avoid any further rise, the French government quickly stabilized the franc de facto at 3.92¢ on December 26, and then returned de jure to gold at the same rate on June 25, 1928.

At the end of 1926, while the franc was now pegged, France was not yet on a genuine gold standard. Officially, and de jure, the franc was still set at the prewar par, when one gold ounce had been set at approximately 100 francs. But now, at the new pegged value, the gold ounce, in foreign exchange, was worth 500 francs. Obviously, no one would now deposit gold at a French bank in return for 100 paper francs, thereby wiping out 80 percent of his assets. Also, the Bank of France (which was a privately owned firm) could not buy gold at the current expensive rate, for fear that the French government might decide, after all, to go back to gold de jure at a higher rate, thereby inflicting a severe loss on its gold holdings. The government, however, did agree to indemnify the bank for any losses it might incur in foreign exchange transactions; in that way, Bank of France stabilization operations could only take place in the foreign exchange market.

The French government and the Bank of France were now committed to pegging the franc at 3.92¢. At that rate, francs were purchased in a mighty torrent on the foreign exchange market, forcing the Bank of France to keep the franc at 3.92¢ by selling massive quantities of newly issued francs for foreign exchange. In that way, foreign exchange holdings of the Bank of France skyrocketed rapidly, rising from a minuscule sum in the summer of 1926 to no less than $1 billion in October of the following year. Most of these balances were in the form of sterling (in bank deposits and short-term bills), which had piled up on the continent during the massive British monetary inflation of 1926 and now moved into French hands with the advent of upward speculation in the franc, and with continued inflation of the pound. Willy-nilly, and against their will, therefore, the French found themselves in the same boat as the rest of Europe: on the gold-exchange or gold-sterling standard.

If France had gone onto a genuine gold standard at the end of 1926, gold would have flowed out of England to France, forcing contraction in England and forcing the British to raise interest rates. The inflow of gold into France and the increased issue of francs for gold by the Bank of France would also have temporarily lowered interest rates there. As it was, French interest rates were sharply lowered in response to the massive issue of francs, but no contraction or tightening was experienced in England; quite the contrary.

Moreau, Rist, and the other Bank of France officials were alert to the dangers of their situation, and they tried to act in lieu of the gold standard by reducing their sterling balances, partly by demanding gold in London, and partly by exchanging sterling for dollars in New York.

This situation put considerable pressure upon the pound, and caused a drain of gold out of England. In the classical gold-standard era, London would have responded by raising the bank rate and tightening credit, stemming or even reversing the gold outflow. But England was committed to an unsound, inflationist policy, in stark contrast to the old gold system. And so, Norman tried his best to use muscle to prevent France from exercising its own property rights and redeeming sterling in gold, and absurdly urged that sterling was beneficial for France, and that they could not have too much sterling. On the other hand, he threatened to go off gold altogether if France persisted—a threat he was to make good four years later. He also invoked the spectre of France’s World War I debts to Britain. He tried to get various European central banks to put pressure on the Bank of France not to take gold from London. The Bank of France found that it could sell up to £3 million a day without attracting the angry attention of the Bank of England; but any more sales than that would call forth immediate protest. As one official of the Bank of France said bitterly in 1927, “London is a free gold market, and that means that anybody is free to buy gold in London except the Bank of France.”

Why did France pile up foreign exchange balances? The anti-French myth of the Establishment charges that the franc was undervalued at the new rate of 3.92¢, and that therefore the ensuing export surplus brought foreign exchange balances into France. The facts of the case were precisely the reverse. Before World War I, France traditionally had a deficit in its balance of trade. During the post–World War I inflation, as usually occurs with fiat money, the foreign exchange rate rose more rapidly than domestic prices, since the highly liquid foreign exchange market is particularly quick to anticipate and discount the future. Therefore, during the French hyperinflation, exports were consistently greater than imports.

What then accounted for the amassing of sterling by France? The inflow of capital into France. During the French hyperinflation, capital had left France in droves to escape the depreciating franc, much of it finding a haven in London. When Poincaré put his monetary and budget reforms into effect in 1926, capital happily reversed its flow, and left London for France, anticipating a rising or at least a stable franc.

In fact, rather than being obstreperous, the French, succumbing to the blandishments and threats of Montagu Norman, were overly cooperative, much against their better judgment. Thus, Norman warned Moreau in December 1927 that if he persisted in trying to redeem sterling in gold, Norman would devalue the pound. In fact, Poincaré prophetically warned Moreau in May 1927 that sterling’s position had weakened and that England might all too readily give up on its own gold standard. And when France stabilized the franc de jure at the end of June 1928, foreign exchange constituted 55 percent of the total reserves of the Bank of France (with gold at 45 percent), an extraordinarily high proportion of that in sterling. Furthermore, much of the funds deposited by the Bank of France in London and New York were used for stock market loans and fueled stock speculation; worse, much of the sterling balances were recycled to repurchase French francs, which continued the accumulation of sterling balances in France. It is no wonder that Dr. Palyi concludes that

[i]t was at Norman’s urgent request that the French central bank carried a weak sterling on its back well beyond the limit of what a central bank could reasonably afford to do under the circumstances. No other major central bank took anything like a similar risk (percentage-wise).

Monty Norman could neutralize the French, at least temporarily. But what of the United States? The British, we remember, were counting heavily on America’s continuing price inflation, to keep British gold out of American shores. But instead, American prices were falling slowly but steadily during 1925 and 1926, in response to the great outpouring of American products. The gold-exchange standard was being endangered by one of its crucial players before it had scarcely begun!

So, Norman decided to fall back on his trump card, the old magic of the Norman-Strong connection. Benjamin Strong must, once more, rush to the rescue of Great Britain! After Norman turned for help to his old friend Strong, the latter invited the world’s four leading central bankers to a top-secret conference in New York in July 1927. In addition to Norman and Strong, the conference was attended by Deputy Governor Rist of the Bank of France and Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, governor of the German Reichsbank. Strong ran the American side with an iron hand, keeping the Federal Reserve Board in Washington in the dark, and even refusing to let Gates McGarrah, chairman of the board of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, attend the meeting. Strong and Norman tried their best to have the four nations embark on a coordinated policy of monetary inflation and cheap money. Rist demurred, although he agreed to help England by buying gold from New York instead of London, (that is, drawing down dollar balances instead of sterling). Strong, in turn, agreed to supply France with gold at a subsidized rate: as cheap as the cost of buying it from England, despite the far higher transportation costs.

Hjalmar Schacht

Schacht was even more adamant, expressing his alarm at the extent to which bank credit expansion had already gone in England and the United States. The previous year, Schacht had acted on his concerns by reducing his sterling holdings to a minimum and increasing the holdings of gold in the Reichsbank. He told Strong and Norman: “Don’t give me a low [interest] rate. Give me a true rate. Give me a true rate, and then I shall know how to keep my house in order.” Thereupon, Schacht and Rist sailed for home, leaving Strong and Norman to plan the next round of coordinated inflation themselves. In particular, Strong agreed to embark on a mighty inflationary push in the United States, lowering interest rates and expanding credit—an agreement which Rist, in his memoirs, maintains had already been privately concluded before the four-power conference began. Indeed, Strong gaily told Rist during their meeting that he was going to give “a little coup de whiskey to the stock market.” Strong also agreed to buy $60 million more of sterling from England to prop up the pound.

Pursuant to the agreement with Norman, the Federal Reserve promptly launched its greatest burst of inflation and cheap credit in the second half of 1927. This period saw the largest rate of increase of bank reserves during the 1920s, mainly due to massive Fed purchases of U.S. government securities and of bankers’ acceptances, totaling $445 million in the latter half of 1927. Rediscount rates were also lowered, inducing an increase in bills discounted by the Fed. Benjamin Strong decided to sucker the suspicious regional Federal Reserve banks by using Kansas City Fed Governor W.J. Bailey as the stalking horse for the rate-cut policy. Instead of the New York Fed initiating the rediscount rate cut from 4 percent to 3.5 percent, Strong talked the trusting Bailey into taking the lead on July 29, with New York and the other regional Feds following a week or two later. Strong told Bailey that the purpose of the rate cuts was to help the farmers, a theme likely to appeal to Bailey’s agricultural region. He made sure not to tell Bailey that the major purpose was to help England pursue its inflationary gold-exchange policy.

The Chicago Fed, however, balked at lowering its rates, and Strong got the Federal Reserve Board in Washington to force it to do so in September. The isolationist Chicago Tribune angrily called for Strong’s resignation, charging correctly that discount rates were being lowered in the interests of Great Britain.

After generating the burst of inflation in 1927, the New York Fed continued, over the next two years, to do its best: buying heavily in prime commercial bills of foreign countries, bills endorsed by foreign central banks. The purpose was to bolster foreign currencies, and to prevent an inflow of gold into the U.S. The New York Fed also bought large amounts of sterling bills in 1927 and 1929. It frankly described its policy as follows:

We sought to support exchange by our purchases and thereby not only prevent the withdrawal of further amounts of gold from Europe but also, by improving the position of the foreign exchanges, to enhance or stabilize Europe’s power to buy our exports.

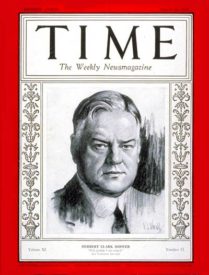

If Strong was the point man for the monetary inflation of the late 1920s, the Coolidge administration was not far behind. Pittsburgh multimillionaire Andrew W. Mellon, secretary of the Treasury throughout the Republican era of the 1920s, was long closely allied with the Morgan interests. As early as March 1927, Mellon assured everyone that “an abundant supply of easy money” would continue to be available, and he and President Coolidge repeatedly acted as the “capeadores of Wall Street,” giving numerous newspaper interviews urging stock prices upward whenever prices seemed to flag. And in January 1928, the Treasury announced that it would refund a 4.5-percent Liberty Bond issue, falling due in September, in 3.5-percent notes. Within the administration, Mellon was consistently Strong’s staunchest supporter. The only sharp critic of Strong’s inflationism within the administration was Secretary of Commerce Herbert C. Hoover, only to be met by Mellon’s denouncing Hoover’s “alarmism” and interference.

The motivation for Benjamin Strong’s expansionary policy of the late 1920s was neatly summed up in a letter by one of his top aides to one of Montagu Norman’s top henchmen, Sir Arthur Salter, then director of Economic and Financial Organization for the League of Nations. The aide noted that Strong, in the spring of 1928, “said that very few people indeed realized that we were now paying the penalty for the decision which was reached early in 1924 to help the rest of the world back to a sound financial and monetary basis.”

Similarly, a prominent banker admitted to H. Parker Willis in the autumn of 1926 that bad consequences would follow America’s cheap-money policy, but that “that cannot be helped. It is the price we must pay for helping Europe.” Of course, the price paid by Strong and his allies was not so “onerous,” at least in the short run, when we note, as Dr. Clark pointed out, that the cheap credit aided especially those speculative, financial, and investment banking interests with whom Strong was allied—notably, of course, the Norman complex. The British, as early as mid-1926, knew enough to be appreciative. Thus, the influential London journal, The Banker, wrote of Strong that “no better friend of England” existed. The Banker praised the “energy and skillfulness that he has given to the service of England,” and exulted that “his name should be associated with that of Mr. [Walter Hines] Page as a friend of England in her greatest need.”

On the other hand, Morgan partner Russell C. Leffingwell was not nearly as sanguine about the Strong-Norman policy of joint credit expansion. When, in the spring of 1929, Leffingwell heard reports that Monty was getting “panicky” about the speculative boom in Wall Street, he impatiently told fellow Morgan partner Thomas W. Lamont, “Monty and Ben sowed the wind. I expect we shall all have to reap the whirlwind. . . . I think we are going to have a world credit crisis.”

Unfortunately, Benjamin Strong was not destined personally to reap the whirlwind. A sickly man, Strong in effect was not running the Fed throughout 1928, finally dying on October 16 of that year. He was succeeded by his handpicked choice, George L. Harrison, also a Morgan man but lacking the personal and political clout of Benjamin Strong.

At first, as in 1924, Strong’s monetary inflation was temporarily successful in accomplishing Britain’s goals. Sterling was strengthened, and the American gold inflow from Britain was sharply reversed, gold flowing outward. Farm produce prices, which had risen from an index of 100 in 1924 to 110 the following year, and had then slumped back to 100 in 1926 and 99 in 1927, now jumped up to 106 the following year. Farm and food exports spurted upward, and foreign loans in the United States were stimulated to new heights, reaching a peak in mid-1928. But, once again, the stimulus was only temporary. By the summer of 1928, the pound sterling was sagging again. American farm prices fell slightly in 1929, and agricultural exports fell in the same year. Foreign lending slumped badly, as both domestic and foreign funds poured into the booming American stock market.

The stock market had already been booming by the time of the fatal injection of credit expansion in the latter half of 1927. The Standard and Poor’s industrial common stock index, which had been 44.4 at the beginning of the 1920s boom in June 1921, had more than doubled to 103.4 by June 1927. Standard and Poor’s rail stocks had risen from 156.0 in June 1921 to 316.2 in 1927, and public utilities from 66.6 to 135.1 in the same period. Dow Jones industrials had doubled from 95.1 in November 1922 to 195.4 in November 1927. But now, the massive Fed credit expansion in late 1927 ignited the stock market fire. In particular, throughout the 1920s, the Fed deliberately and unwisely stimulated the stock market by keeping the “call rate,” that is, the interest rate on bank call loans to the stock market, artificially low. Before the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, the call rate frequently had risen far above 100 percent, when a stock market boom became severe; yet in the historic and virtually runaway stock market boom of 1928–29, the call rate never went above 10 percent. The call rates were controlled at these low levels by the New York Fed, in close collaboration with, and at the advice of, the Money Committee of the New York Stock Exchange. The stock market, during 1928 and 1929, went into overdrive, virtually doubling these two years. The Dow went up to 376.2 on August 29, 1929, and Standard and Poor’s industrials rose to 195.2, rails to 446.0, and public utilities to 375.1 in September. Credit expansion always concentrates its booms in titles to capital, in particular stocks and real estate, and in the late 1920s, bank credit propelled a massive real estate boom in New York City, in Florida, and throughout the country. These included excessive mortgage loans and construction from farms to Manhattan office buildings.

The stock market had already been booming by the time of the fatal injection of credit expansion in the latter half of 1927. The Standard and Poor’s industrial common stock index, which had been 44.4 at the beginning of the 1920s boom in June 1921, had more than doubled to 103.4 by June 1927. Standard and Poor’s rail stocks had risen from 156.0 in June 1921 to 316.2 in 1927, and public utilities from 66.6 to 135.1 in the same period. Dow Jones industrials had doubled from 95.1 in November 1922 to 195.4 in November 1927. But now, the massive Fed credit expansion in late 1927 ignited the stock market fire. In particular, throughout the 1920s, the Fed deliberately and unwisely stimulated the stock market by keeping the “call rate,” that is, the interest rate on bank call loans to the stock market, artificially low. Before the establishment of the Federal Reserve System, the call rate frequently had risen far above 100 percent, when a stock market boom became severe; yet in the historic and virtually runaway stock market boom of 1928–29, the call rate never went above 10 percent. The call rates were controlled at these low levels by the New York Fed, in close collaboration with, and at the advice of, the Money Committee of the New York Stock Exchange. The stock market, during 1928 and 1929, went into overdrive, virtually doubling these two years. The Dow went up to 376.2 on August 29, 1929, and Standard and Poor’s industrials rose to 195.2, rails to 446.0, and public utilities to 375.1 in September. Credit expansion always concentrates its booms in titles to capital, in particular stocks and real estate, and in the late 1920s, bank credit propelled a massive real estate boom in New York City, in Florida, and throughout the country. These included excessive mortgage loans and construction from farms to Manhattan office buildings.

The Federal Reserve authorities, now concerned about the stock market boom, tried feebly to tighten the money supply during 1928, but they failed badly. The Fed’s sales of government securities were offset by two factors: (a) the banks shifting their depositors from demand deposits to “time” deposits, which required a much lower rate of reserves, and which were really savings deposits redeemable de facto on demand, rather than genuine time loans, and (b) more important, the fruit of the disastrous Fed policy of virtually creating a market in bankers’ acceptances, a market which had existed in Europe but not in the United States. The Fed’s policy throughout the 1920s was to subsidize and in effect create an acceptance market by standing ready to buy any and all acceptances sold by certain favored acceptance houses at an artificially cheap rate. Hence, when bank reserves tightened as the Fed sold securities in 1928, the banks simply shifted to the acceptance market, expanding their reserves by selling acceptances to the Fed. Thus, the Fed’s selling of $390 million of securities was partially offset, during latter 1928, by its purchase of nearly $330 million of acceptances. The Fed’s sticking to this inflationary policy in 1928 was now made easier by adopting the fallacious “qualitativist” view, held as we have seen also by Herbert Hoover, that the Fed could dampen down the boom by restricting loans to the stock market while merrily continuing to inflate in the acceptance market.

In addition to pouring in funds through acceptances, the Fed did nothing to tighten its rediscount market. The Fed discounted $450 million of bank bills during the first half of 1928; it finally tightened a bit by raising its rediscount rates from 3.5 percent at the beginning of the year to 5 percent in July. After that, it stubbornly refused to raise the rediscount rate any further, keeping it there until the end of the boom. As a result, Fed discounts to banks rose slightly until the end of the boom instead of declining. Furthermore, the Fed failed to sell any more of its hoard of $200 million of government securities after July 1928; instead, it bought some securities on balance during the rest of the year.

Why was Fed policy so supine in late 1928 and in 1929? A crucial reason was that Europe, and particularly England, having lost the benefit of the inflationary impetus by mid-1928, was clamoring against any tighter money in the U.S. The easing in late 1928 prevented gold inflows from the U.S. from getting very large. Britain was again losing gold; sterling was again weak; and the United States once again bowed to its wish to see Europe avoid the consequences of its own inflationary policies.

Leading the inflationary drive within the administration were President Coolidge and Treasury Secretary Mellon, eagerly playing their roles as the capeadores of the bull market on Wall Street. Thus, when the stock market boom began to flag, as early as January 1927, Mellon urged it onward. Another relaxing of stock prices in March spurred Mellon to call for and predict lower interest rates; again, a weakening of stock prices in late March induced Mellon to make his statement assuring “an abundant supply of easy money which should take care of any contingencies that might arise.” Later in the year, President Coolidge made optimistic statements every time the rising stock market fell slightly. Repeatedly, both Coolidge and Mellon announced that the country was in a “new era” of permanent prosperity and permanently rising stock prices. On November 16, the New York Times declared that the administration in Washington was the source of most of the bullish news and noted the growing “impression that Washington may be depended upon to furnish a fresh impetus for the stock market.” The administration continued these bullish statements for the next two years. A few days before leaving office in March 1929, Coolidge called American prosperity “absolutely sound” and assured everyone that stocks were “cheap at current prices.”

The clamor from England against any tighter money in the U.S. was driven by England’s loss of gold and the pressure on sterling. France, having unwillingly piled up $450 million in sterling by the end of June 1928, was anxious to redeem sterling for gold, and indeed sold $150 million of sterling by mid-1929. In deference to Norman’s threats and pleas, however, the Bank of France sold that sterling for dollars rather than for gold in London. Indeed, so cowed were the French that (a) French sales of sterling in 1929–31 were offset by sterling purchases by a number of minor countries, and (b) Norman managed to persuade the Bank of France to sell no more sterling until after the disastrous day in September 1931 when Britain abandoned its own gold-exchange standard and went on to a fiat pound standard.

Meanwhile, despite the great inflation of money and credit in the U.S., the massive increase in the supply of goods in the U.S. continued to lower prices gradually, wholesale prices falling from 104.5 (1926=100) in November 1925 to 100 in 1926, and then to 95.2 in June 1929. Consumer price indices in the U.S. also fell gradually in the late 1920s. Thus, despite Strong’s loose money policies, Norman could not count on price inflation in the U.S. to bail out his gold-exchange system. Montagu Norman, in addition to pleading with the U.S. to keep inflating, resorted to dubious short-run devices to try to keep gold from flowing out to the U.S. Thus, in 1928 and 1929, he would sell gold for sterling to raise the sterling rate a bit, in sales timed to coincide with the departure of fast boats from London to New York, thus inducing gold holders to keep the precious metal in London. Such short-run tricks were hardly adequate substitutes for tight money or for raising bank rate in England, and weakened long-run confidence in the pound sterling.

In March 1929, Herbert Clark Hoover, who had been a powerful secretary of commerce during the Republican administrations of the 1920s, became president of the United States. While not as intimately connected as Calvin Coolidge, Hoover long had been close to the Morgan interests. Mellon continued as secretary of the Treasury, with the post of secretary of state going to the longtime top Wall Street lawyer in the Morgan ambit, Henry L. Stimson, disciple and partner of J.P. Morgan’s personal attorney, Elihu Root. Perhaps most important, Hoover’s closest, but unofficial adviser, whom he regularly consulted three times a week, was Morgan partner Dwight Morrow.

In March 1929, Herbert Clark Hoover, who had been a powerful secretary of commerce during the Republican administrations of the 1920s, became president of the United States. While not as intimately connected as Calvin Coolidge, Hoover long had been close to the Morgan interests. Mellon continued as secretary of the Treasury, with the post of secretary of state going to the longtime top Wall Street lawyer in the Morgan ambit, Henry L. Stimson, disciple and partner of J.P. Morgan’s personal attorney, Elihu Root. Perhaps most important, Hoover’s closest, but unofficial adviser, whom he regularly consulted three times a week, was Morgan partner Dwight Morrow.

Hoover’s method of dealing with the inflationary boom was to try not to tighten the money supply, but to keep bank loans out of the stock market by a jawbone method then called “moral suasion.” This too was the preferred policy of the new governor of the Federal Reserve Board in Washington, Roy A. Young. The fallacy was to try to restrict credit to the stock market while keeping it abundant to “legitimate” commerce and industry. Using methods of intimidation of business honed when he was secretary of commerce, Hoover attempted to restrain stock loans by New York banks, tried to induce the president of the New York Stock Exchange to curb speculation, and warned leading editors and publishers about the dangers of high stock prices. None of these superficial methods could be effective.

Professor Beckhart added another reason for the adoption of the ineffective policy of moral suasion: that the administration had been persuaded to try this tack by the old manipulator, Montagu Norman. Finally, by June 1929, the moral suasion was at last abandoned, but discount rates were still not raised, so that the stock market boom continued to rage, even as the economy in general was quietly but inexorably turning downward. Secretary Mellon once again trumpeted our “unbroken and unbreakable prosperity.” In August, the Federal Reserve Board finally agreed to raise the rediscount rate to 6 percent, but any tightening effect was more than offset by the Fed’s simultaneously lowering its acceptance rate, thereby once again giving an inflationary fillip to the acceptance market. One reason for this resumption of acceptance inflation, after it had been previously reversed in March, was, yet again, “another visit of Governor Norman. Thus, once more, the cloven hoof of Montagu Norman was able to give its final impetus to the boom of the 1920s. Great Britain was also entering upon a depression, and yet its inflationary policies resulted in a serious outflow of gold in June and July. Norman was able to get a line of credit of $250 million from a New York banking consortium, but the outflow continued through September, much of it to the United States. Continuing to help England, the New York Fed bought heavily in sterling bills from August through October. The new subsidization of the acceptance market, mostly foreign acceptances, permitted further aid to Britain through the purchase of sterling bills.

A perceptive epitaph on the qualitative-credit politics of 1928–29 was pronounced by A. Wilfred May:

Once the credit system had become infected with cheap money, it was impossible to cut down particular outlets of this credit without cutting down all credit, because it is impossible to keep different kinds of money separated in water-tight compartments. It was impossible to make money scarce for stock-market purposes, while simultaneously keeping it cheap for commercial use. . . . When Reserve credit was created, there was no possible way that its employment could be directed into specific uses, once it had flowed through the commercial banks into the general credit stream.

Written by Murray N. Rothbard for the Mises Institute ~ December 29, 2021

[Excerpt from Murray N. Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II (Auburn, AL: Mises Institute, 2005), part 4, pp. 400–24.]