History Suggests This Spells Trouble for Stocks.

We’re witnessing history: the first meaningful decline in U.S. money supply in 90 years.

We’re witnessing history: the first meaningful decline in U.S. money supply in 90 years.

Volatility has been the name of the game on Wall Street since this decade began. Since 2020, the iconic Dow Jones Industrial Average, broad-based S&P 500, and growth-focused Nasdaq Composite, have bounced back and forth between bear and bull markets.

These wild fluctuations have left investors to question what’s next for stocks. Although there isn’t any one indicator that can, with 100% accuracy, forecast what’s to come in the short run for Wall Street, there are quite a few economic datapoints that have an uncanny track record of predicting short-term directional movements in the Dow Jones, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite. One such metric that should be raising some eyebrows is U.S. money supply.

History is being made before investors’ very eyes…

There are two money supply metrics that tend to be widely followed: M1 and M2.

M1 money supply encompasses all cash and coins in circulation, as well as traveler’s checks and demand deposits in a checking account. In short, it’s money that’s very easily accessible and can be spent at a moment’s notice. Meanwhile, M2 money supply factors in everything in M1 and adds savings accounts, money market accounts, and certificates of deposit (CDs) below $100,000. In other words, it’s money you can still get to, but it requires extra effort to access it. M2 money supply is what’s currently ringing alarm bells on Wall Street.

M2 money supply has expanded with little interruption for more than 150 years. This isn’t a surprise given that the U.S. economy has also expanded fairly steadily when examined over multidecade periods. As the U.S. economy grows, more capital is needed to facilitate consumer and enterprise transactions.

Using data available via the U.S. Census Bureau and St. Louis Federal Reserve, Reventure Consulting CEO Nick Gerli tracked the year-over-year movements in M2 money supply dating back to 1870, as you can see in the post above.

Over the past 153 years, there have only been five instances where U.S. M2 money supply has contracted by at least 2%: the late 1870s, 1893, 1921, during the Great Depression, and 2023 (M2 money supply is currently 3.86% below its all-time high, set in July 2022). Take note that Gerli’s post is seven months old, which is why his chart depicts a decline of only 2% in 2023.

In the prior four instances where M2 declined by at least 2%, we witnessed a panic (1893) and three depressions (late 1870s, 1921, and the Great Depression). With M2 shrinking for the first time since the Great Depression, history would suggest that trouble awaits the U.S. economy and stock market.

The caveat to the above is that U.S. money supply exploded higher by an all-time record 26% on a year-over-year basis during the COVID-19 pandemic. While it is possible that the current 3.86% decline in M2 from July 2022 is nothing more than a reversion to the mean after a massive expansion of U.S. money supply via fiscal and monetary stimulus, history intimates that it’s more likely foreshadowing a deflationary recession to come.

Additional money metrics offer a potential warning for Wall Street

The concern for Wall Street is that M2 money supply is far from the only money-based metric signaling potential trouble to come. Two other money-focused datapoints allude to the growing likelihood of a U.S. recession — and stocks have, historically, fared poorly following the declaration of an official recession.

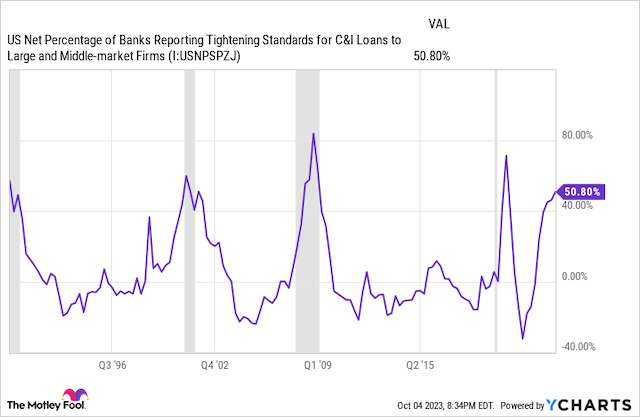

Every quarter, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors releases its “Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices,” which, as its name implies, examines the landscape and sentiment surrounding domestic bank lending practices.

Every quarter, the Federal Reserve Board of Governors releases its “Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices,” which, as its name implies, examines the landscape and sentiment surrounding domestic bank lending practices.

As of the July release, the net percentage of U.S. banks reporting tightening standards for commercial and industrial (C&I) loans to large and middle-market firms jumped to 50.8%. C&I loans are typically short-term, collateralized loans that businesses use for working capital, major projects, and acquisitions.

What this datapoint shows is that more than half of all U.S. banks are making it tougher for mid-sized and large companies to access loans to fund acquisitions and major projects. This would almost certainly lead to a slowdown or reversal in hiring, merger and acquisition activity, and even innovation. In short, it’s a recipe for an economic slowdown.

Furthermore, anytime the net percentage of domestic banks tightening their standards on C&I loans has surpassed 50% since 1990, a U.S. recession has occurred.

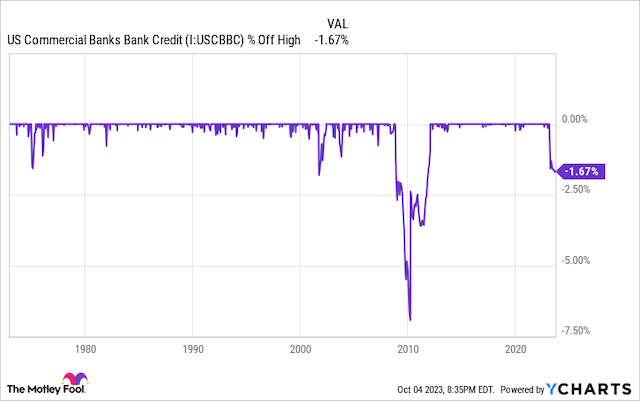

The other worrisome money metric is U.S. commercial bank credit, which encompasses the aggregate of loans, leases, and Treasury/agency securities, such as mortgage-backed securities, held by commercial banks.

The other worrisome money metric is U.S. commercial bank credit, which encompasses the aggregate of loans, leases, and Treasury/agency securities, such as mortgage-backed securities, held by commercial banks.

Similar to M2 money supply, aggregate bank lending tends to rise on an almost uninterrupted basis over long periods. Banks are incentivized to make loans to cover the costs of taking in and holding deposits.

There have, however, been four instances over the past 50 years where commercial bank credit has declined by at least 1.5% from an all-time high: 1975, 2001, 2009-2010, and 2023. Currently, commercial bank credit is 1.67% below its record high, set in mid-February 2023, which confirms that banks are less willing to lend money.

The three previous instances where commercial bank credit dipped by at least 1.5% saw the benchmark S&P 500 lose around half of its value, with the Nasdaq Composite getting hit even harder.

Widening the lens tells a very different story

Admittedly, none of the above figures paints a positive picture for the U.S. economy or stock market in the coming weeks, months, or quarters. But when investors widen their lens beyond just a couple of quarters, things look markedly different.

To address the obvious, recessions are a normal and inevitable part of the economic cycle. If one were to occur in the not-too-distant future, it would mark the 13th official downturn in the U.S. economy since the end of World War II.

However, only three of the 12 recessions that have occurred after World War II have lasted at least 12 months, and none has endured more than 18 months. Recessions are short-lived events that pale in comparison to the length of economic expansions.

The same holds true for the stock market. Although there have been 39 double-digit percentage declines in the S&P 500 since the start of 1950 — an average of one meaningful decline every 1.89 years — all but the most recent (the 2022 bear market) have been put into the rearview mirror.

The same holds true for the stock market. Although there have been 39 double-digit percentage declines in the S&P 500 since the start of 1950 — an average of one meaningful decline every 1.89 years — all but the most recent (the 2022 bear market) have been put into the rearview mirror.

Further, a comprehensive analysis by Bespoke Investment Group found that the average bull market since September 1929 has outlasted the average bear market by a factor of 3.5. Whereas the 27 bear markets over the past 94 years have lasted an average of 286 calendar days, the typical bull market has endured 1,011 calendar days over the same timeline.

There’s no question the Dow Jones Industrial Average, S&P 500, and Nasdaq Composite are going to hit rough patches from time to time. But widening the lens shows that these “rough patches” are short-lived and, historically, provide the perfect opportunity for patient investors to pounce on high-quality businesses at a discount.

Though various money metrics may portend trouble in the coming quarters, smart investors are following the money to big gains over the long run.

Written by Sean Williams for The Motley FOOL ~ October 8, 2023