NOTE: As has been known by me for many years, Herr Schacht was an ancestor of the Editor/Publisher’s tax attorney and accountant, Raymond Schacht of New York. (Ed.)

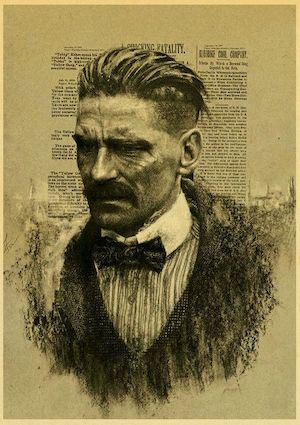

Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht

July 22, 2012 ~ I am an avid reader of monetary history. Of late I have been focusing on the monetary events of the 1920s and 1930s. By learning from the maelstrom that riled the global financial scene during those two tumultuous decades, I aim to better understand present circumstances because there are many similarities between then and now.

I’ve just finished a fascinating book published in 1955 entitled Confessions of The Old Wizard. It is the autobiography of Hjalmar Horace Greeley Schacht, whose improbable name reflects his North Schleswig ancestry and his fathers admiration of an American newspaper editor.

For those not familiar with him, Schacht is generally given credit for ending in 1923 the Weimar Republic hyperinflation and putting Germany once again on a sound monetary footing, commendable feats which earned him the nickname The Old Wizard. He did this first as Commissioner of the Currency for the Finance Ministry and thereafter as President of the Reichsbank. For these achievements, he received worldwide acclaim as well as fame, if that word accurately describes the popular attention and respect given to a skilled central banker.

Schachts autobiography contains many stories and anecdotes, including those of his meetings with dozens of famous people. But Schachts account of a meeting with Benjamin Strong is one I found particularly important, shocking even.

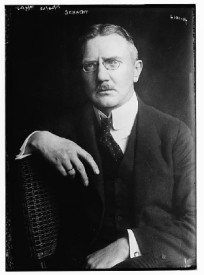

Strong was president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York from its creation in 1914 until his death in 1928. Strong, Schacht, Montague Norman of England and Émile Moreau of France were the most powerful and influential central bankers of their time.

Strong was in effect the head of the Federal Reserve because the New York bank back then dominated the system. Reforms in the 1930s diminished somewhat the power of the New York bank, but to this day it remains vitally important because it alone of the 12 Federal Reserve banks transacts with other central banks. For example, there is reportedly some Bundesbank gold stored in the Federal Reserve Bank of New Yorks vault near Wall Street, which is it often said contains the worlds largest accumulation of gold.

It is the same vault Schacht visited during one of his trips to New York to meet with Benjamin Strong. Here is how Schacht relates this remarkable event.

Another amusing incident arose from the fact that the Reichsbank maintained a not inconsiderable gold deposit in the Federal Reserve Bank in New York. Strong was proud to be able to show us the vaults which were situated in the deepest cellar of the building and remarked:

Now, Herr Schacht, you shall see where the Reichsbank gold is kept.

While the staff looked for the hiding place of the Reichsbank gold we went through the vaults. We waited several minutes: at length we were told: Mr. Strong, we cant find the Reichsbank gold.

Strong was flabbergasted but I comforted him. Never mind: I believe you when you say the gold is there. Even if it werent you are good for its replacement.”

A. Hitler and H. Schacht

Shocking, isnt it. Clearly, it is bad enough that the Reichsbank gold could not be found nor, according to Schachts account, did Strong offer to find it. But regardless whether it could not be located due to bad recordkeeping by the Federal Reserve or because the gold was not in the vault is not as significant as Schachts nonchalant response to what he astonishingly calls an amusing incident. Where is his outrage that the Reichsbank gold could not be located? Why is there no worry about the disposition of the gold and its safety? After all, as President of the Reichsbank, he had responsibility for all of its assets, of which gold is by far the most important.

What can we learn from this event? Schacht apparently considered friendship to other central bankers and his membership in their exclusive club to be a higher priority than his responsibility as guardian of a nations gold. Schacht did not question Strong, so the actual location and true circumstances of the Reichsbank gold remained unknown. This astonishing incident would not have occurred if the Reichsbank had instead stored the gold in its own vault.

What can we learn from this event? Schacht apparently considered friendship to other central bankers and his membership in their exclusive club to be a higher priority than his responsibility as guardian of a nations gold. Schacht did not question Strong, so the actual location and true circumstances of the Reichsbank gold remained unknown. This astonishing incident would not have occurred if the Reichsbank had instead stored the gold in its own vault.

Written by James Turk and published at Gold Money, June 30, 2012.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml