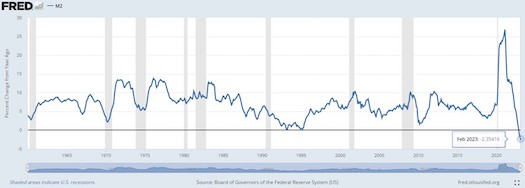

U.S. money supply is falling at its fastest rate since the 1930s, a red flag for the economy and financial markets.

U.S. money supply is falling at its fastest rate since the 1930s, a red flag for the economy and financial markets.

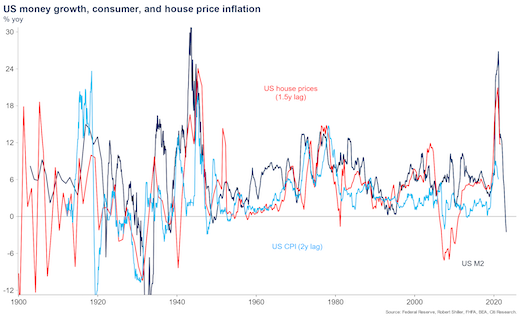

Money supply has now been shrinking year-on-year since December, an unprecedented development in modern times that should make investors sit up and take notice – growth, asset prices and inflation could all weaken.

It is largely a consequence of the reversal of the liquidity generated by massive post-pandemic fiscal and monetary stimulus, the Federal Reserve shrinking its balance sheet via quantitative tightening, falling bank deposits, and weak demand for and provision of credit.

All else equal, it is a sign the Fed has no need to raise interest rates further. Given the lag of one to two years between money supply changes and the impact on asset prices and inflation, it may even be a sign that the U.S. central bank should be cutting rates.

Fed data on Tuesday showed that M2 money supply, a benchmark measure of how much cash and cash-like assets is circulating in the U.S. economy, fell a non-seasonally adjusted 2.2% to $21.099 trillion in February from the same period a year earlier.

In seasonally-adjusted terms, M2 money supply fell 2.4% from the same month last year to $21.063 trillion.

That was before the March failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank – both in the top 25 banks in the country – which fanned fears of a credit crunch, stoked market volatility, and prompted temporary emergency liquidity measures and backstops from the Fed worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

That was before the March failures of Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank – both in the top 25 banks in the country – which fanned fears of a credit crunch, stoked market volatility, and prompted temporary emergency liquidity measures and backstops from the Fed worth hundreds of billions of dollars.

Matt King at Citi in London, an expert on capital flows and liquidity, says if money supply growth can reasonably be seen to expand liquidity and fuel inflationary pressures, then the opposite should be true.

“M2 is a driver of broader asset price inflation, consumer inflation, equities, and real estate. It is sending quite a negative signal for all of those now, and will likely feed through to broader economic weakness,” he said.

MONEY, THAT’S WHAT I WANT

MONEY, THAT’S WHAT I WANT

M2 measures the nation’s overall stash of cash, coins, bills, bank deposits, and money market funds, and is basically the broadest measure of cash and cash-like liquid assets.

Money growth started slowing in early 2021 as base effects from the fiscal and monetary splurge to tackle the coronavirus pandemic kicked in. The trend accelerated as the Fed’s QT program picked up, and M2 contracted in December for the first time since the 1940s.

Shrinking money supply is rare but has been buried this year in the blizzard of market volatility around the Fed’s aggressive interest rate hikes, and more recently, the banking shock that has rocked rates and bond markets, and the central bank’s expectations.

More broadly, money supply has been out of policymaking fashion for the best part of 30 years, since central banks started using interest rates as the primary tool to achieve their consumer price inflation targets, usually around 2%.

A mix of factors in the 1980s and 1990s – including falling inflation, financial deregulation, the ‘financialisation’ of economies – helped loosen the link between money targeting and GDP growth. Money supply was considered a less reliable basis for policymaking.

YOU NEVER GIVE ME YOUR MONEY

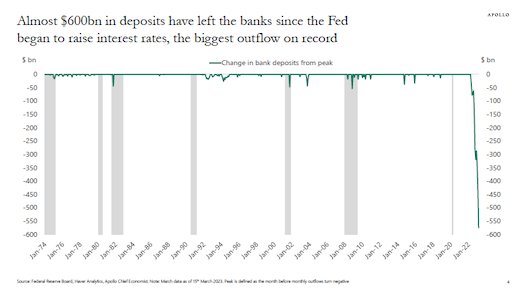

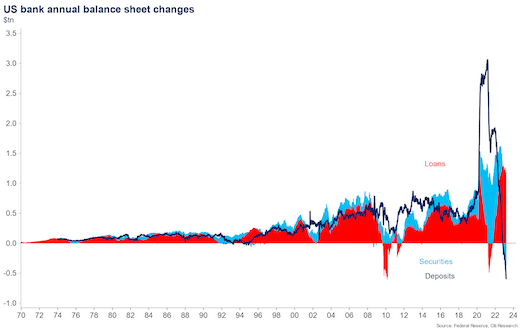

The post-COVID stimulus surge and the Fed’s equally dramatic push to tighten policy – mainly via super-charged rate hikes, but also QT – has had a profound effect on banks’ customer deposits, reserve balances, and general liquidity in the system.

The banking sector shock intensified some of these trends. By some measures, retail deposit outflows from U.S. banks have been the biggest on record, particularly from smaller and regional banks.

Estimates vary, but hundreds of billion dollars have fled these institutions. If deposits fall, banks must reduce lending to match their assets and liabilities, so the impact on M2 money supply is less clear-cut.

Estimates vary, but hundreds of billion dollars have fled these institutions. If deposits fall, banks must reduce lending to match their assets and liabilities, so the impact on M2 money supply is less clear-cut.

In addition, much of that deposit flow has gone into money market funds, which now boast a record aggregate balance of more than $5 trillion. But money market funds form part of M2.

Further muddying the picture, money market fund flows make up a chunk of the $2 trillion-plus that institutions park daily at the Fed’s overnight reverse repo facility.

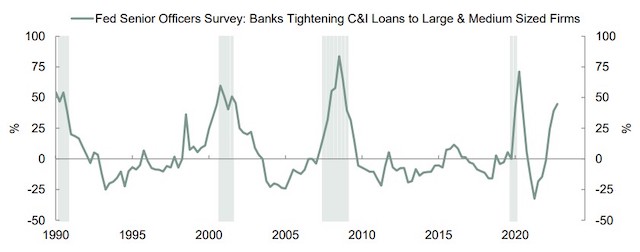

There’s still a lot of cash in the system, but much of it is stagnant. This fits with data showing that demand for credit was already weakening, and lending standards already tightening, even before the banking shock.

Lawrence Goodman, founder and president of the Center for Financial Stability, a think tank, says too much liquidity was allowed to slosh around the system for too long, and the effects of that unwind are now being felt. Investors should ignore money supply at their peril.

“Net-net, money is being extinguished. Money metrics send signals about what is happening in the economy. If money and inflation are falling at this pace, the Fed should be done raising rates,” Goodman said.

Written by Jamie McGeever for Reuters ~ March 30, 2023