An intriguing conversation with monetary scholar James Turk.

Money. It’s the one thing that is never far from most people’s minds. We strive after it and fight over it. We can have enough, or too little, but never too much. Yet few give even a fleeting thought to what it is, or whether what is generally considered to be money is sound or unsound.

What is sound money?

What is sound money?

“Sound money,” he says, “is an asset. Something physical that you can exchange for something else. When you receive it, you know you’re receiving a tangible good.”

So it isn’t scraps of paper (a term that for our purposes we will use to include the modern equivalent, bits and bytes in an account)?

“No, in the absence of it being convertible to something physical, paper is merely a “fiat” (unbacked) currency, a promise on the part of the government. You don’t know whether that promise is reliable and of course, promises can be broken.”

The problem, he adds, is that “there is a big misconception that currency is money. It isn’t. Money is a means of communication; currency is just a convenient representation of money that enables us to take care of our needs by buying and selling goods and services in our free market society.”

Many things have been employed as media of exchange over the millennia as needed, from seashells to barley, from tea to human slaves. But in the end, people settled on precious metals, particularly gold and silver, as the ideal.

Why? Because the precious metals are uniquely suited to the job. Money, in order to function efficiently, must be portable, which lets out blocks of marble. It should not decay, a drawback with barley. And it should be divisible, which is why we don’t use computer chips.

Most of all, it should be relatively scarce, hard to find, and difficult to refine, thus preventing people of a criminal bent from creating money in their home workshops. Gold meets all of these criteria. You can carry some in your pocket, its value can be determined by weight, and it endures forever. Nearly all of the gold ever mined is still around.

Moreover, there isn’t much of it. As Jim points out, “All of the above-ground stock of gold, about 155,000 tons, would fill approximately 3¼ Olympic-size swimming pools. Or the bottom fifth of the Washington Monument.” Thus, Jim adds, gold “has been chosen by the marketplace over thousands of years as the most liquid asset. It’s the only commodity produced for accumulation. All others are produced for consumption.”

Sound Money in the Constitution

The founders of the American Republic knew the importance of sound money when they wrote the Constitution, which in Article I, Section 8 gives to Congress the right to “coin money” and “regulate the value thereof.” It doesn’t say “print.”

That distinction is one that the document’s authors well understood, Jim says, since their own experience with paper money was fresh in their minds. They had been forced to finance the Revolutionary War with paper continentals. So many had been printed that the U.S. was hit by inflation, and then by hyperinflation. In the end, continentals became worthless, and those who had trusted in them were left with nothing.

In order to avoid a repeat of this fiasco, the founders regularized a money, the dollar, that was something tangible, of real value. The Coinage Act of 1792, one of the first acts of Congress, defined the dollar as 371¼ grains of pure silver. The fledgling nation was on the silver standard, where it would remain for the next hundred years.

This, Jim points out, was what they meant when they wrote the phrase regulate the value into the Constitution; it was to determine the ratio of silver to gold. “The Act established the ratio of the prices of gold to silver,” Jim says, “which is important because at that time, some countries were on a gold standard like Britain and some on silver, like much of Europe and China.” Thus the value of gold was set at 15 times that of the silver dollar.

Even with metal backing, though, the dollar wasn’t immune from fluctuations in value. This was especially true in the late 19th century, when there was a sudden influx of silver into the market. In other words, inflation, which some wanted to counter by switching to a standard based on gold, since it was scarcer.

That, Jim says, led to William Jennings Bryan, who “was an easy money guy and wanted to retain the silver standard,” giving his famous “Cross of Gold” speech.

That, Jim says, led to William Jennings Bryan, who “was an easy money guy and wanted to retain the silver standard,” giving his famous “Cross of Gold” speech.

Bryan and his followers lost and, in 1900, the country went on a gold standard. A dollar was defined as 23.22 grains of gold, and the price of gold was set at $20.67/ounce. This standard—with one tweaking—endured for almost three-quarters of a century.

This is the history of a country with a sound monetary system. When did it all start to go wrong? we asked Jim.

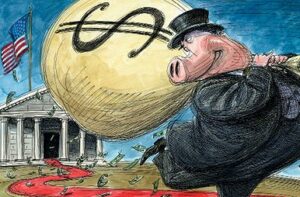

Primarily, he replies, “with the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. The purpose of the Federal Reserve was to centralize the system and ultimately get more control over gold.” It also allowed the central banks to realize their longtime objective, to gain control over the currency, which allowed them to expand the credit market and dramatically increase profits. Oh yes, and incidentally to engineer the massive inflation with which we have been saddled ever since.

We have all been brainwashed by politicians and the media into believing an ugly untruth: that rising prices are inevitable, and that inflation of two or three percent is low. Neither is the case, not when compared to an economy built around a sound currency. And the Fed killed sound currency by taking sensible restraints off the central banks, i.e. itself.

Want proof? The numbers don’t lie. There are a lot of ways of figuring this, but let’s consider the most common way of evaluating price changes, the CPI method. This takes a basket of goods and services that one dollar will buy in a given year and compares it with the cost of the same goods and services in another. In 1913, what cost $1 in 1800 could be had for 79 cents. In other words, the value of the buck had actually increased, by more than 20%. That’s pre-Fed.

In contrast, what cost $1 in 1913 went for $19.63 in 2005! Since the creation of the Federal Reserve, which is supposed to efficiently manage the economy, the dollar has lost 95% of its purchasing power.

What caused this dramatic turnaround? Let’s return to 1913. At that point, having placed themselves firmly in the driver’s seat, the banks began engaging in very dubious lending practices. Because they had awarded themselves a newfound control of the monetary system, “fractional reserve banking” (lending out more than you hold in reserve) could be pushed to new heights.

The Wheels Come Off

Things went bonkers during the First World War. Afterward, as Jim puts it, “the extra dollars printed during the war kick-started the fractional reserve banking machine, producing a rip-roaring credit expansion.” The now-familiar result was the Roaring 20s: “Stocks and real estate soared, as the masses discovered the joys of speculating with borrowed funds.”

After the crash of 1929, those who had any savings left reacted intelligently. Realizing that paper dollars were unsound, they turned them in for gold en masse, or as Jim says, “No longer satisfied with money substitutes, they wanted money itself.”

Too bad for them. “U.S. banks, the gold in their vaults inadequate to meet depositors’ demands, began to die… the fractional reserve engine was thrown into reverse, as the remaining banks called in old loans and stopped making new ones. Capital-starved businesses began to fail, and newly unemployed workers stopped spending. Prices fell sharply… causing more businesses to close, in a downward spiral that looked, for a while, to have no end.” The Great Depression had arrived.

Franklin Roosevelt felt he had to take some dramatic steps. He realized that the “dollar had become very debased, relative to gold. It was no longer realistic for gold to be worth $20.67 an ounce, so he devalued the dollar by 69%, redefining it as equal to only 13.71 grains of gold, thereby setting a new price for gold of $35.” He also outlawed the private ownership of gold.

Franklin Roosevelt felt he had to take some dramatic steps. He realized that the “dollar had become very debased, relative to gold. It was no longer realistic for gold to be worth $20.67 an ounce, so he devalued the dollar by 69%, redefining it as equal to only 13.71 grains of gold, thereby setting a new price for gold of $35.” He also outlawed the private ownership of gold.

Why? we asked. Because privately owned gold “was too important in checking the banks from expanding credit without any kind of restriction.” In addition, the government was able to improve its own economic position, since it paid citizens $20.67 for coins that were revalued to $35. Or, to put it another way, the dollars people got were immediately devalued by nearly 70%. It was “theft, pure and simple,” in Jim’s words.

Naturally, FDR didn’t put it quite that way. He claimed, Jim says, that the country needed to become the sole custodian of gold “in order to keep the monetary system on an even keel.”

Sure.

In fact, though, there was an attempt at creating a sound world monetary system at the Bretton Woods Conference in July 1944. Though World War II was still on, the 44 allied nations knew that victory was only a matter of time, and so their representatives gathered in New Hampshire to hammer out an agreement as to the rules of trade in the post-war period.

The U.S. stood alone among the allies (and the axis powers, for that matter), in that its economy had not been decimated by war. It was clearly in the ascendant as the planet’s premier power, and thus its currency was established as the world’s reserve, with most other nations’ currencies tied to it.

Concurrently, everyone accepted $35/ounce gold but, as Jim points out, Bretton Woods actually served to make gold “appear less important than it really is.”

How so? “Because instead of gold being used as a means of clearing between nations when they engaged in global trade, the dollar was going to be used instead. While at that time the dollar was as ‘good as gold’ because of the gold standard, it was still a gold substitute. And it circulated as a gold substitute. But it was merely a promise to pay gold, and,” Jim reminds us again, “a promise can be broken.”

Which it was. Though Bretton Woods maintained FDR’s “even keel” for two decades, the whole thing fell apart when Lyndon Johnson tried to finance both the Vietnam War and the Great Society without asking the American public to foot the bill for either. He just turned on the printing presses and began creating boatloads of “money” out of thin air, a policy with which the Fed was only too happy to cooperate.

Today we live with the consequences of the Johnson economic plan—further compounded by every Congress and presidential administration since—only more so. Of the 95% loss in the dollar’s value since 1913, 70% has been accrued since 1971.

What happened in 1971? The Fed’s ability to inflate currency became absolute. In order for that to happen, something had to give, and what gave was the gold standard. Faced with runaway inflation, President Nixon chose to devalue the dollar, from $35 to $38 per ounce of gold, and to no longer define it as a specific weight of the metal, a move endorsed by the other major industrialized nations.

That was later raised to $42.22 and then finally, says Jim, “the world’s governments threw in the towel, allowing their currencies to sink against gold, with the U.S. removing Depression-era restrictions that barred gold ownership by its citizens.” Henceforth, we would have fiat currency, and nothing but.

The Barbarous Relic

The Barbarous Relic

Although Nixon’s abandonment of the gold standard was a capitulation to bankers who wanted the freedom to create “money” out of thin air, in unlimited amounts, he couldn’t sell it as a defeat, so he recast it as “the most significant monetary agreement in the history of the world.” Nixon hailed it as a triumph that would deliver us from the evil influence of speculators in gold, and thus ended the gold standard once termed a “barbarous relic” by John Maynard Keynes. Not for nothing did Nixon once remark, “We are all Keynesians now.”

Predictably, gold took off after it was allowed to float free—or, more precisely, the dollar and its purchasing power sank—to over $850 an ounce in 1980. Although a two-decade bear market followed, with gold trading sideways, it never again fell below $250.

Meanwhile, politicians ran up more and more debt, as tax revenues failed to keep pace with ever-increasing government spending. Instead of trying to curb spending, Washington simply allowed the currency presses to roll and the dollar steadily to sink in value due to the resultant inflation. The discipline on money creation imposed by the gold standard has been removed.

For twenty years, as the stock market and then the housing market boomed in the U.S. (and around much of the rest of the world), easy money—of the paper variety, that is—was seen as a good thing. Savings were out, speculation was in, and the Greenspan Fed kept on priming the pump, dropping interest rates close to zero.

The worlds of finance and politics are now so entwined that even presidents are merely “serving their vested interests,” says Jim, “those who put them in power, which are the bankers. Because once you break the link with the bankers, the government doesn’t have the ability to borrow whatever it wants.”

Neither party wants this particular dance to end, as government gets to inflate rather than tax and banks get to ring up the profits. “That’s why we have these massive deficits. There is no monetary restraint on the government.”

And today, Jim says, “It’s not that the price of gold is going up, the dollar is going down. Gold still has the same purchasing power. Even though the dollar is not fixed as a weight of gold, gold is still the standard by which goods and services are measured. Against every currency. What’s happened since 1971 is exactly what happened during the War of Independence, the monetary turmoil that caused the founders to make gold and silver the money of this land. We’re reliving what the framers of the Constitution didn’t want us to have to go through again. So we’re ignoring their wisdom.”

We may have learned a thing or two in the past two hundred years, but we’ve forgotten the importance of sound money. “Go back to the provisions of the Constitution,” Jim says. “It wasn’t perfect, but it was better than what we have today, which is ultimately going to lead to the collapse of the dollar, just as the continental collapsed more than two centuries ago. The problems are so daunting that the politicians would rather cheat and lie and manipulate the current system, intervene, restrict freedoms, put on capital controls, and do whatever else they think they can get away with, to keep the dollar bubble from popping.”

So all they’re likely to do is settle for cheaper dollars, we suggested.

“Right,” Jim says. “Which is why they’re not reporting M3 anymore,” referring to the discontinuance earlier this year of the publication of M3, the broadest measure of the money supply. In other words, we’re now being kept in the dark as to how much fiat currency is being pumped into the system, how many dollars are being created out of thin air.

The Treasury Department ho-hummed the event, saying it was no big deal, that it just wasn’t cost-effective to continue compiling the numbers. And they also have some prime seafront Arizona property for sale.

“Back in the old days,” Jim says, “disclosure was used to maintain confidence in the currency. You could see how much gold was in the vault, how many dollars were being created. By eliminating M3, the Fed’s going down an entirely different road. Lack of disclosure is the main component and that, in time, destroys confidence in the currency.”

We’re not going back to the old days, are we?

Not likely, in Jim’s opinion. “That would require leadership to do the right thing—re-establish Constitutional money—and the will to do this we don’t have in Washington.”

Of course, we may be forced back into a sound monetary situation by a U.S. currency collapse, an eventuality Jim regards as a matter of when, not if. All fiat currencies inevitably collapse, he points out, because you can’t pretend indefinitely to create something of value out of nothing.

The dollar has thus far escaped that fate because for half a century it has functioned as the reserve currency of the world, and other nations hold too much of it to allow it to seek its true worth. It has been artificially propped up. But at some point that will change, as everyone’s dollar holdings are continually eaten away by inflation, and the dollar will go into steep decline and inevitable collapse. That’s what Jim believes.

“My generation,” Jim says, “was taught in school the phrase, ‘not worth a continental,’ a saying that became current after the collapse of that currency. I expect that our children and grandchildren will learn a different one: ‘not worth a dollar’.”

Sounds painful to us, we said.

For many it will be, Jim says, but “the pain will be suffered by people who believe the government’s promises, who don’t prepare for the collapse. If you prepare for the worst, and the worst happens, you’re not going to be suffering. With the Depression, a lot of people had prepared for it and lived well through the Depression. That’s why people have to buy gold and silver.”

Gold and silver are sound money, paper currency is not. It’s that simple. Precious metals have represented a storehouse of value for thousands of years, still do, and will probably continue to do so far into the future.

Written by Doug Hornig and published by 24h Gold ~ October 20, 2006.

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml