‘A Powerful Signal of Recessions’ Has Wall Street’s Attention

You can try to play down a trade war with China. You can brush off the impact of rising oil prices on corporate earnings.

You can try to play down a trade war with China. You can brush off the impact of rising oil prices on corporate earnings.

But if you’re in the business of making economic predictions, it has become very difficult to disregard an important signal from the bond market.

The so-called yield curve is perilously close to predicting a recession — something it has done before with surprising accuracy — and it’s become a big topic on Wall Street.

Terms like “yield curve” can be mind-numbing if you’re not a bond trader, but the mechanics, practical impact and psychology of it are fairly straightforward. Here’s what the fuss is all about.

First, the mechanics

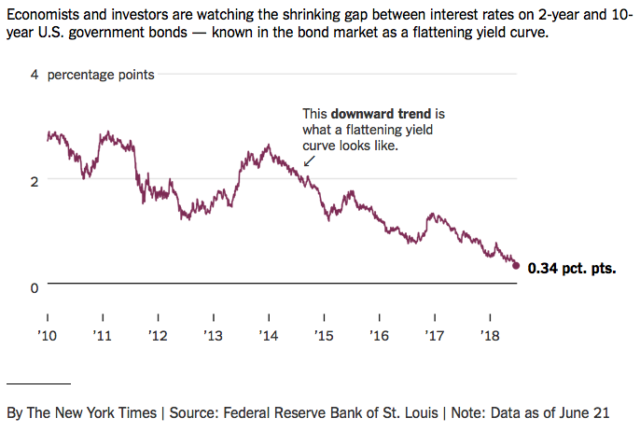

The yield curve is basically the difference between interest rates on short-term United States government bonds, say, two-year Treasury notes, and long-term government bonds, like 10-year Treasury notes.

Typically, when an economy seems in good health, the rate on the longer-term bonds will be higher than short-term ones. The extra interest is to compensate, in part, for the risk that strong economic growth could set off a broad rise in prices, known as inflation. Lately, though, long-term bond yields have been stubbornly slow to rise — which suggests traders are concerned about long-term growth — even as the economy shows plenty of vitality.

At the same time, the Federal Reserve has been raising short-term rates, so the yield curve has been “flattening.” In other words, the gap between short-term interest rates and long-term rates is shrinking.

The gap between two-year and 10-year United States Treasury notes is roughly 0.34 percentage points. It was last at these levels in 2007 when the United States economy was heading into what was arguably the worst recession in almost 80 years.

The gap between two-year and 10-year United States Treasury notes is roughly 0.34 percentage points. It was last at these levels in 2007 when the United States economy was heading into what was arguably the worst recession in almost 80 years.

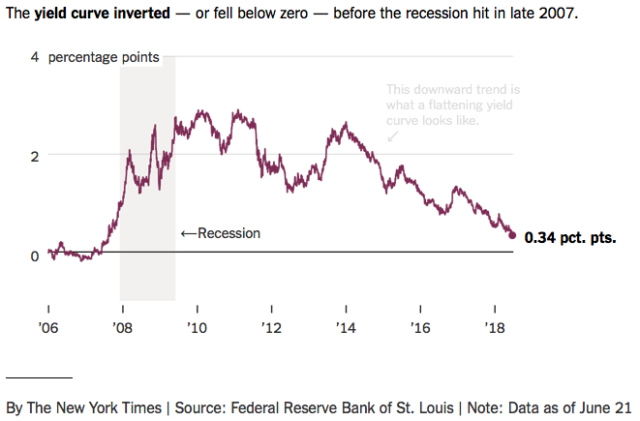

As scary as references to the financial crisis sound, flattening alone does not mean that the United States is doomed to slip into another recession. But if it keeps moving in this direction, eventually long-term interest rates will fall below short-term rates.

When that happens, the yield curve has “inverted.” An inversion is seen as “a powerful signal of recessions,” as the president of the New York Fed, John Williams, said this year, and that’s what everyone is watching for.

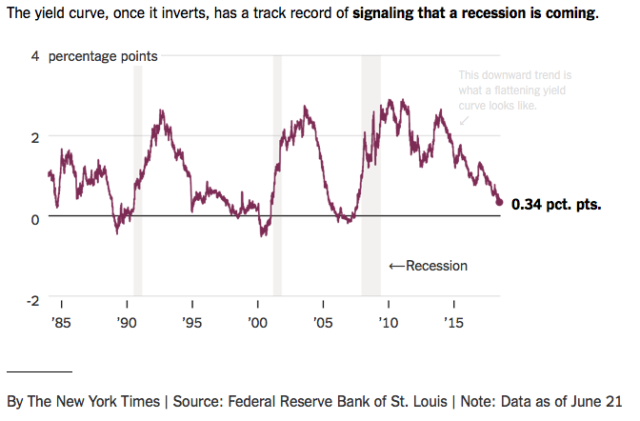

Every recession of the past 60 years has been preceded by an inverted yield curve, according to research from the San Francisco Fed. Curve inversions have “correctly signaled all nine recessions since 1955 and had only one false positive, in the mid-1960s, when an inversion was followed by an economic slowdown but not an official recession,” the bank’s researchers wrote in March.

Even if it hasn’t happened yet, the move in that direction has Wall Street’s attention.

“For economists, of course it’s always been traditionally a very good signal of directionality of the economy,” said Sonja Gibbs, senior director of capital markets at the Institute of International Finance. “That’s why everyone is bemoaning the flattening of the yield curve.”

“For economists, of course it’s always been traditionally a very good signal of directionality of the economy,” said Sonja Gibbs, senior director of capital markets at the Institute of International Finance. “That’s why everyone is bemoaning the flattening of the yield curve.”

Recession? Really?

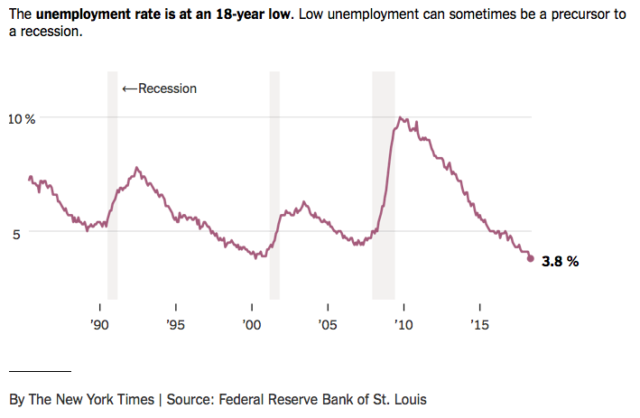

Sure, it seems like a strange time to be worried about recession. Unemployment is at an 18-year low, corporate investment is picking up steam, and consumer spending shows signs of rebounding.

Some economists on Wall Street think the economy could be growing at around a nearly 5 percent annualized clip this quarter. But if the current economic vigor is only reflecting a short-term stimulus coming from the Trump administration’s tax cut, then some kind of slowdown is to be expected.

“It’s very hard to see what’s going to goose the economy further from these levels,” Ms. Gibbs said.

“It’s very hard to see what’s going to goose the economy further from these levels,” Ms. Gibbs said.

And the financial markets can sometimes sniff out problems with the economy before they show up in the official economic snapshots published on G.D.P. and unemployment. Another notable yield curve inversion occurred in February 2000, just before the stock market’s dot-com bubble burst.

In that sense, the government bond market isn’t alone. Stocks have been in a sideways struggle since the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index last peaked on Jan. 26. Returns on corporate bonds are negative, as are some key commodities tied to industrial activity.

An important caveat to the predictive power of the yield curve is that it can’t predict precisely when a recession will begin. In the past the recession has come in as little as six months, or as long as two years, after the inversion, the San Francisco Fed’s researchers note.

In other words, there’s a reason to look at the yield curve skeptically, despite its prowess at predicting recessions.

The new fear gauge.

As in all market moves, perceptions of its significance mean the yield curve can sometimes become a feedback loop.

If enough investors begin to grow concerned about a recession, they will most likely put more and more money into the safety of long-term government bonds. That buying binge would likely help flatten, or invert, the yield curve.

Then people will write articles about the curve’s sending a stronger signal on recession. And that could, in turn, drive even more people to buy into long-term bonds. Rinse. Repeat.

There’s also a practical impact.

But it’s not just psychology. The yield curve helps determine some of the decisions that are the most crucial to the health of the American economy.

Specifically, the flattening yield curve makes banking, which is basically the business of borrowing money at short-term rates and lending it at long-term rates, less profitable. And if the yield curve inverts, it means lending money becomes a losing proposition.

Either way, the flow of lending is likely to be curtailed. And in the United States, where borrowed money is the lifeblood of economic activity, that can slam the brakes on economic growth.

The Fed’s hand.

There is an argument to be made against reading too much into the yield curve’s moves — and it hangs on the idea that, rather than the free market, central banks have had a big influence on both the long-term and short-term rates.

Since the last recession, central banks bought trillions of dollars of government bonds as they tried to push long-term interest rates lower in order to lend a helping hand to the economy.

Even though they’re reversing course now, central banks still own massive amounts of those bonds, and that may be keeping long-term interest rates lower than they would otherwise be.

Also, the Federal Reserve has been raising short-term interest rates since December 2015 and has indicated it will keep doing so this year.

So if long-term rates were pushed lower by central bank bond buying, and now short-term rates are being pushed higher as the Fed tightens its monetary policy, the yield curve has nowhere to go but flatter.

“In the current environment, I think it’s a less reliable indicator than it has been in the past,” said Matthew Luzzetti, a senior economist at Deutsche Bank.

Written by Matt Phillips and published on The New York Times ~ June 26, 2018

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

FAIR USE NOTICE: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of environmental, political, human rights, economic, democracy, scientific, and social justice issues, etc. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U. S. C. Section 107, the material on this site is distributed without profit to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for research and educational purposes. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml